|

| View of Reykjavik from Hallgrímskirkja |

This summer I had the chance to visit Iceland for the Nineteenth Biennial International Congress of the New Chaucer Society. I am still processing the experiences I had, which loom like fantastical peaks in my memory. I went a week ahead of the conference so that I would have time to explore Reykjavik and spend some time in the surrounding country as well. As the conference grew nearer, I began to run into more and more familiar faces around the city, and it was exciting to feel that sense of connectedness in this beautiful new place. The conference was fantastic. I heard excellent papers and conversed with friends old and new. The energy of the conversations I had is helping to motivate me as I work through the final period of dissertation writing/revising. The congress also included excursions, so I got to see some stunning things both in and out of the city. The landscape in Iceland is startlingly, unbelievably beautiful. I asked my Romanticist friend if the word "sublime" applied, and she said that it did. Driving through the country there feels like driving out of this world and into a world of myth. I fell in love with Iceland. I immersed myself in sagas before and during my trip, and then the landscape of the sagas vivified and challenged and confirmed everything that I had read or wanted to read.

|

| Black sand beach at Vik (The sea stacks may be trolls who were petrified by the sunrise) |

An incredible feature of the landscape is that every place I visited was interwoven with stories. These stories bridge the gaps between myth and history with growing grass and trickling water and surging lava. A cliff was a troll who'd been petrified by the rising sun. A pool of water once splashed with the bodies of women hurled there to drown for adultery or incest or infanticide. The terrain there seems indifferent to humans (though maybe not to elves). Its beauty delights and beckons, but it seems like it isn't really meant for us either. I cannot imagine how the first settlers survived. Yet the stories that surround every topographical feature manage to lend it a narrative texture. Reykjavik, for example, exists where it does because Ingólfur Arnarson threw his high seat pillars into the ocean in 874 when he saw Iceland's coastline materialize on the horizon. The pillars landed in a spot made steamy by hot springs, leading to the name Reykjavik, meaning "smoky bay."

|

| Turf houses at Keldur |

|

| Detail from Njáls saga fragment, c. 1300 |

But architectural wonders are not the primary attractions in Iceland. The people who settled there built no massive castles or cathedrals. And much of what they did build has disappeared under layers of time. The remains of a longhouse, for example, feature in the Settlement Museum. The ruins were discovered during a construction project, and the museum is carved out around them in an underground space. As incredible as this museum is, most of the impressive buildings I saw are not medieval, but modern: the Harpa concert hall, Hallgrímskirkja church. The most dazzling remains of times past in Iceland are manuscripts and the recorded sagas and laws and history and myths they contain. And those narratives are written onto the landscape as surely as any wood or stone constructions could be.

Outside of the city, the landscape seems to swallow up built structures with its shifting and boisterous geological demeanor. In the landscape of Þingvellir, fissures and cracks in the earth proliferate and separating plates reveal a path between the continents. In such a space, who could hope to locate the famed rock where The Law Speaker stood to recite the laws to the people? Grass-covered outlines of booths are the only traces of the lively gatherings that once crowded the space. Yet the story of the law rock and of the yearly general assemblies that took place there from 930 to 1798 still brings us to Þingvellir en masse. The description of the general assembly as a place to adjudicate disputes and visit friends and relatives is vivid in texts like Njál's saga. The land is steeped in the intersected narratives of geological and historical time.

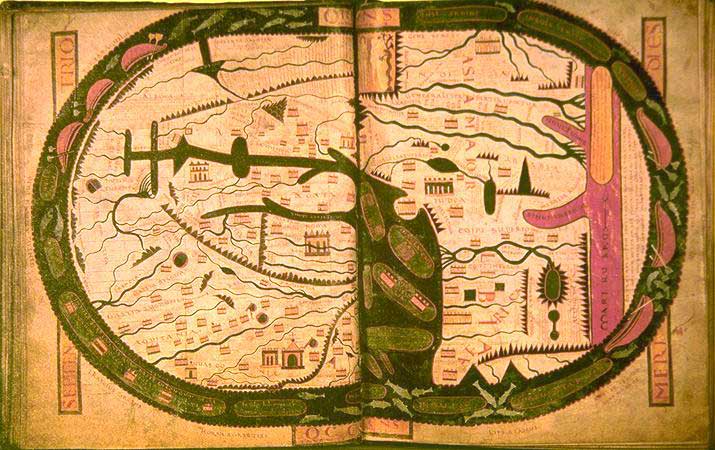

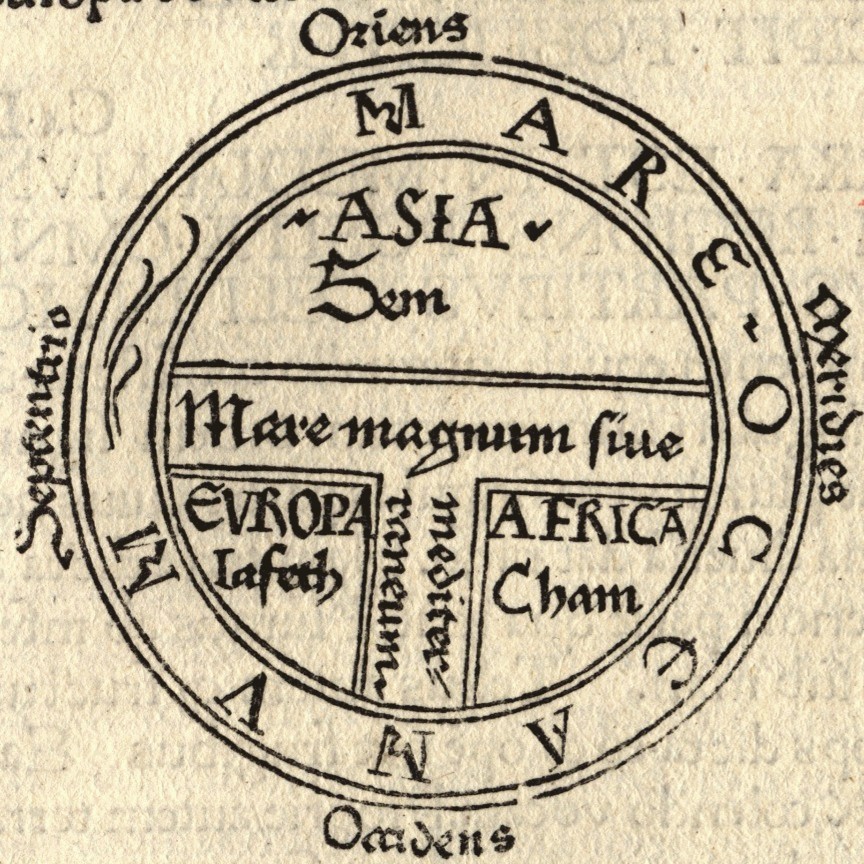

The multiplicity of temporal narratives written onto the landscape there reminds me of medieval mappa mundi, which feature Biblical and classical and contemporary history arranged spatially over the world. Medieval travel narratives (and Icelandic sagas, for that matter) connect their stories to locations, while the maps connect the locations to stories, but in each case there remains a strong sense that narratives and places are mutually constitutive. Since I was presenting a paper on this very idea, the location of the conference and my adventures there ended up connecting to my presentation in ways that I couldn't have anticipated. In my paper, "'By Sun and by Shadow': Narrative Mapping

in The Canterbury Tales," I considered the frame of the The Canterbury Tales as a travel narrative and thought about the function of the tales in relation to travel. I guess it was inevitable that my own experience of traveling would link to my paper.

|

| Walking behind Seljalandsfoss |

In one memorable moment, for example, as I scrambled into a cavern behind the waterfall called Seljalandsfoss, I found myself rethinking how time is conceived in The Canterbury Tales. The power of the water was palpable, so

palpable that I emerged from the experience drenched. Water rolls off of the

mountain inexorably; currents and gravity converge so that the water travels

forcefully in one direction, a teleological natural wonder. (Though I was later told that the wind is sometimes so strong that it can send a waterfall upward ...) Anyone who gazes

into the heart of a waterfall can see that its movements are beyond human

control. Harry Bailey evokes such an image in the prologue to the Man of Law’s Tale, when he laments

wasted time:

Lordinges, the tyme wasteth night and day,

And steleth from us, what prively slepinge,

And what thurgh necligence in our wakinge,

As dooth the streem, that turneth never agayn,

Descending fro the montaigne in-to playn. (21-25).

The host’s description of time expresses the movement from one moment to the next in a strikingly geographical way. Time is like a stream, whose current only moves one way. The progression of time is like gravity, flowing down the mountain in a way that we mortals are powerless to fight. We are always in the flow of time; it’s not so visible or tangible as the waterfall, but its movement is just as relentless. The pilgrims’ trip to Canterbury might be meandering and, ultimately, incomplete, but time moves along as they tell their tales and we read them.

This description of time as a geographical feature connects temporal movement, often seen as linear and narrative (at least in many Western cultures), with the more spatial and visual. Since the frame of The Canterbury Tales is a travel narrative, this connection between narrative and landscape makes sense. Medieval travel narratives, all along the spectrum from real to fictional, follow a model of connecting locations to stories of things that have happened there (or may have happened there). And my travel the week before had been the same. The part of the gorge leading to Seljalandsfoss, for example, is named Troll’s Gorge for an old troll woman who tried to cross it. Other places I visited connect to people and events from the sagas, and the sagas in turn are consistently connected to topographical features that we can visit today. A hill or city or waterfall links us with things that happened there a thousand years ago. Travel narratives more generally serve to yoke stories and locations. Medieval mappae mundi take this connection even further, collapsing past and present by presenting all of their details in

| Babylon and Tower of Babel from Ranulph Higden’s Polychronicon (From the British Library's Medieval Manuscripts Blog) |

I argue that Chaucer's use of narrative mapping in The Canterbury Tales serves to reexamine the ways in which time and space function together in the act of traveling. Chaucer specifically calls attention to the connection between story and travel in the prologues to The Man of Law's Tale and The Parson's Tale. In each prologue, the host notes the position of the sun and the shadows it creates in order to ascertain the time and thus to decide how many tales may yet be told that day. Each tale is told as a result of these calculations, and thus each tale begins with a specific sense of correlation to the journey at hand. Unlike the bits of narrative on mappae mundi, these stories do not directly concern the location of their telling, but instead represent the movement through time and space that constitutes travel itself. To map the progress of these pilgrims, then, is only possible by engaging with acts of storytelling.

|

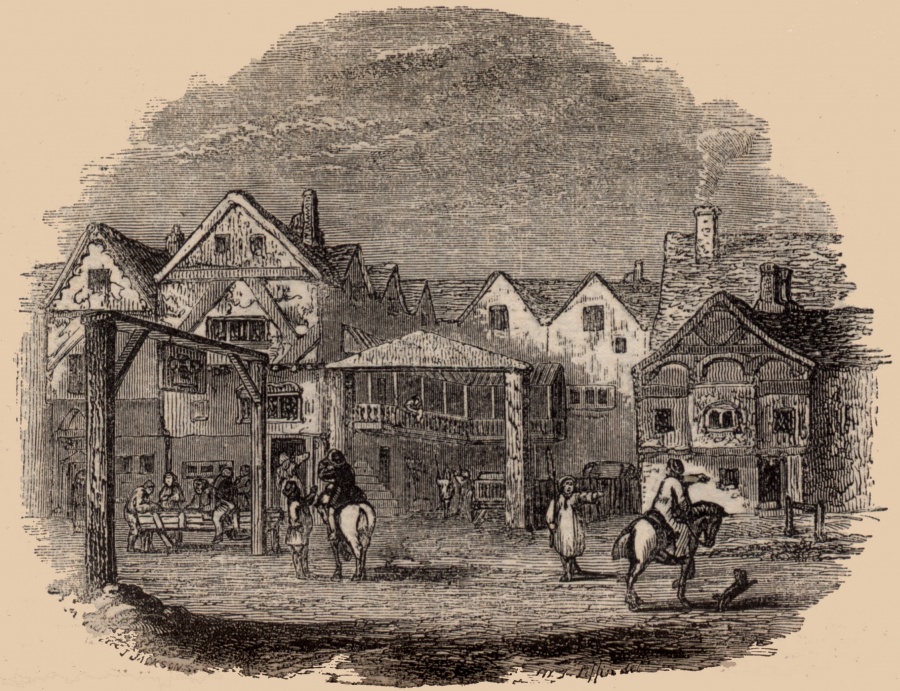

| The Tabard, Urry's edition of Chaucer (1720) (Courtesy of Visualizing Chaucer) |

Because of this lack of topographical detail, the moments when the host does seem to call attention to the surroundings are striking. Before introducing the Man of Law’s Tale, we are told that

Our Hoste sey wel that the brighte sonne

The ark of his artificial day had ronne

The fourthe part, and half an houre, and more;

And though he were not depe expert in lore,

He wiste it was the eightetethe day

Of April, that is messager to May;

And sey wel that the shadwe of every tree

Was as in lengthe the same quantitee

That was the body erect that caused it. (1-9)

|

| Photo from my own pilgrimage to Canterbury in 2011 |

The passage continues for some time, as the host notices many things about the shadows and infers many things about the time on account of what he sees. Josie Bloomfield pointed out last year at the Plymouth Medieval and Renaissance Forum (in a talk titled "Walking with an Astrolabe: Measuring Time on Chaucer’s Pilgrimage") that his information is not particularly accurate and is more cumbersome than it needs to be. If the host wants to know the time, listening to church bells would be much easier. And yet Chaucer chooses to write it this way. The details he includes might not describe a specific location on the journey to Canterbury, but they do describe sun and tree and shadow in order to define a specific point on the journey. As Helen Cooper explains in The English Romance in Time, “A phrase such as ‘a day’s journey’ is in fact tautologous, since ‘journey’ derives from journée, how far can be covered in a day. Distance itself was hard to measure, and the conversion of space into time provided a functional and accessible approximation. The ease of the conversion is itself an indication of how one-dimensional travel appeared, like time itself. The conversion worked in the other direction too, to represent time as space. Dante famously claimed to have had his vision of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven … mid-way along the pathway of his life, in the thirty-fifth year of his allotted seventy” (68). To travel is to move through space and time simultaneously, and to pilgrimage is to ultimately to collapse the two. We go to the place where Becket was killed in the past because that location has meaning for us in the present. The host further connects location to time when he uses the waterfall metaphor I mentioned above. The conclusion of his astronomical musings is to ask the Man of Law to waste no more time and tell his tale. There is some irony in how much time the host spends in trying to move things along, but the sustained focus on scenery and time and story-telling functions to remind us of the connection between travel and narrative in the Tales.

The tale the Man of Law tells is itself full of travel, as Custance sails from east to west and back again. Kathy Lavezzo argues in Angels on the Edge of the World that "since Custance's journey begins in Syria, the cartographic territory evoked in the tale . . . suggests a map of the world" (95). Both we as readers and the pilgrims as listeners can follow Custance’s voyages while the Man of Law describes them. Stories, after all, are a kind of travel, as reading about travel to holy places sometimes functioned as virtual pilgrimage for those who

|

| Detail from Gustaf Tenggren illustration to the Man of Law's Tale (1961) |

The second mention of sun and shadows comes before the Parson’s Tale, which is further removed from physical travel than the Man of Law’s choice of material. In this second instance, the geotemporal reflections in this scene come not from the host, but from the narrator Geoffrey. He begins with reference to the previous tale, which places the observations explicitly between tales:

By that the maunciple hadde his tale al ended,

The sonne fro the south lyne was descended

So lowe, that he nas nat, to my sighte,

Degreës nyne and twenty as in highte.

Foure of the clokke it was tho, as I gesse;

For eleven foot, or litel more or lesse,

My shadwe was at thilke tyme, as there,

Of swich feet as my lengthe parted were

In six feet equal of proportion. (1-9)

|

| My own interaction with sun and mist and flowers at the base of Gullfloss |

… 'Lordings everichoon,

Now lakketh us no tales mo than oon.

Fulfild is my sentence and my decree;

I trowe that we han herd of ech degree.

Almost fulfild is al myn ordinaunce.' (15-19)

The tale-telling is meant to accompany the trip to

Canterbury, so the idea that all but one pilgrim has told a tale and that the

host’s ordinance is almost fulfilled gives us a clear sense of movement. If

this many tales has been told while riding along, they must have been getting

somewhere. And again this knowledge of movement and this request for another

tale comes from observations about the play of the sun on the world, details

about their surroundings so clear that the host could speak up even as the

narrator muses to us about his own shadow.

The Parson’s Tale that follows is, to put it mildly, different from the Man of Law’s. In response to the host’s invitation to give the company a fable, the parson retorts “Thou getest fable noon ytoold for me” (31). And not only is it not a fable, but it’s not even really a tale at all. It’s more of a sermon. While the Man of Law, responding to a similar request from the host, sends us around the world with his narrative, the parson wants us to instead look inward and examine our souls for a different sort of pilgrimage. As he explains,

And jhesu, for his grace, wit me sende

Of thilke parfit glorious pilgrymage

That highte jerusalem celestial. (48-51)

The parson wants to achieve the perfect pilgrimage of

celestial Jerusalem, which isn’t physical but is rather spiritual in nature. Even

though tales like the Man of Law’s don’t

directly relate to the voyage at hand,

they’re still part of a shared game of tale-telling that is associated with the

time it takes to get from one place in England to another. The Parson, on the

other hand, yanks us out of the temporal realm and leads us to a

kind of pilgrimage that is related to a Canterbury pilgrimage spiritually (at

least ideally speaking – some pilgrims seem to have more spiritual reasons than

others), but is distinct in more practical ways. As Helen Cooper notes, “The pathway

of life is also the journey of life; life as quest” (68). We’re all moving from

birth to death, and many hope that death will be followed by a pleasant afterlife. As the narrator in Pearl

just can’t help but try to cross the river in his vision, it’s easy to mistake

geographical movement as the way to achieve that ultimate pilgrimage, but the

parson insistently reminds us that we must look inward and turn our minds to higher things.

It is perhaps telling that a “tale” with so little connection to either

narrative or location follows an extended musing on the visual cues of the

passage of time. We might long for the

eternal, but in the meantime we’re stuck in the temporal realm.

|

| John's vision of Christ and heavenly Jerusalem, Revelation 21: 2-8 from Yates Thompson 10 f. 36 (Courtesy of the British Library) |

As we read these moments where time and space rise to the surface of the Canterbury Tales’ frame narrative only to be followed by tales with an increasingly vague sense of physical locatedness, the connection in narrative between time and space becomes both apparent and richly complex. It is impossible to separate the one from the other, and yet neither is fixed. Whether we read a story or travel to Iceland or just sit and wait, things change. Time passes. The earth shifts, and landscapes are built and rebuilt. The simultaneously uncertain and sure movement of those pilgrims as they wend their way and tell there tales both removes us from time and space and reminds us that we can never escape them. Except, perhaps, in the afterlife.

|

| Layers of lava rock look heavenly to me |