Now that winter is over and green has returned to the land, I am thinking again of the greenwood, something I presented on last fall at the 9th Biennial Conference of the International Association of Robin Hood Studies at Saint Louis University.

I was presenting on a new topic (and one I am still struggling to understand), but one that may have been influenced somewhat by my teaching Shakespeare that semester. As I was preparing my presentation on the ballad of Robin Hood and the Monk, I was teaching Midsummer Night's Dream and As You Like It, both plays involving escape to the world of the greenwood. As You Like It even features Shakespeare's only reference to Robin Hood, when Charles explains that the exiled Duke and his men live in the Forest of Ardenne "like the old Robin Hood of England" (1.1.101). The difference between these plays and the early ballads, however, is in the liminal nature of the greenwood space. Like The Tale of Gamelyn, after which As You Like It's plot was partly based (and one of my cats is named as well), and Anthony Munday's Downfall of Robert, Erle of Huntington and Death of Robert, Erle of Huntington, Shakespeare describes a temporary movement away from urban space. The greenwood in these texts allows for freedom and resolution and the ultimate return to the city. In the early ballads like Robin Hood and the Monk, on the other hand, the greenwood is the permanent residence of the outlaws.

|

| I really love spring |

My paper, "'As light as lef on lynde': Dangerous Play in Robin Hood and the Monk," grappled with the fact that the forest in Robin Hood and the Monk is a space of beauty and joy, and yet the ballad is filled with terrible violence. I felt disturbed by the disjunction between the tone of the ballad and its content. I had been thinking a lot about the ballad as I worked on the Much the Miller's Son page for the Robin Hood Project. It features one of Much's most memorable (and terrible) moments, when Little John murders a monk and Much murders the monk's little page, presumably a child. Yet the opening of the ballad gives us no sense of the carnage to come, but rather invites us into a merry springtime world:

And leves be large and long,

Hit is full mery in feyre foreste

To here the foulys song. (1-4)

[In summer, when the woods are bright,

And leaves are large and long,

It is full merry in fair forest

To hear the birds' song.]

It's May, the season in which lovers and outlaws alike can rejoice, and birdsong fills the forest with music and our hearts with delight. The short ballad (we have 358 lines, and there were originally around 406) spends the first 12 lines, in fact, on how merry the forest is, and then, when we are finally introduced to a character on line 13, it is Little John, announcing that "'This is a merry mornyng'" ['This is a merry morning'] and continuing with more discussion of the joys of summer in the greenwood. The idyllic realm with which the poem opens, however, belies the violence underlying the carefree lifestyle of this outlaw band. One of the earliest extant ballads, Robin Hood and the Monk is best remembered not for the beauty and delight to be found in the greenwood, but instead for the shocking violence perpetrated by the outlaws who reside there. Many men are slain over the course of the ballad, and, in a moment that unsettles modern fans and critics alike, Much beheads a child without a second thought. Although it might seem that the playful tone of the ballad ill-suits such grim content, I have begun to think that the ballad instead promotes a specific kind of violence that is playful in nature, a kind of violence that, like the ballad itself, can trick a person outside of the outlaw band even as it can lead to shame, discomfort, or death. The ballad does not contrast violence with harmony, but instead contrasts varieties of violence to show that merry and playful violence is the most successful for those residing in the greenwood world. This playful violence is in turn indicative of the link between outlaw identity and greenwood space.

|

| "In Somer, when the shawes be sheyne" (Sun through the trees at Letchworth Park) |

'Take twelve of thi wyght yemen,

Well weppynd, be thi side.

Such on wolde thi selfe slon,

That twelve dar not abyde.' (31-4)

['Take twelve of your strong yeomen,

Well armed, by your side.

Such a person as would slay you,

Would not dare face those twelve.']

I suppose you know you’re an outlaw when going to church requires twelve bodyguards. Robin’s rejection of this plan is also a rejection of the group mentality. He separates himself from his men not only by his attitude and his plan to depart from the greenwood, but also by his unwillingness to bring members of the greenwood band with him. His subsequent squabbling with Little John, a character who represents the merry greenwood world, cements his role in this ballad; he is out of sync with the outlaw realm, neither merry nor attuned to the natural world around him. Stephen Knight and Thomas Ohlgren note in their introduction to the text that "[t]he forest setting seems a state of harmony to which the outlaws return after urban disruptions. But just as violence enters this Edenic world, the communal calm of the outlaw band is disrupted by conflict." I would add to this that the conflict comes when Robin is not aligned with the greenwood space and outlaw band; it is this internal "ferly strife" that serves as a catalyst for the larger violence (and notably high body count) of the ballad (51). When Robin and John part, the ballad explains that,

Then Robyn goes to Notyngham,

Hym selfe mornyng allone,

And Litull John to mery Scherwode,

The pathes he knew ilkone. (63-66)

[Then Robin goes to Nottingham,

Mourning to himself alone,

And Little John goes to merry Sherwood,

The paths he knew each one.]

|

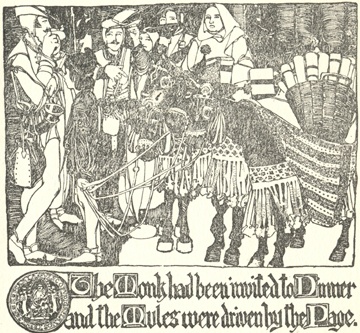

| Howard Pyle image (1883) courtesy of the Robin Hood Project |

Robin’s most violent moment, a scene in which he slays twelve men and wounds “mony a moder son” [many a mother's son] caps off a succession of astonishingly reckless actions on his part. (109). Not only does he head to mass alone, but strolls right in with no disguise and kneels to pray in front of the whole congregation so that “[a]lle that ever were the church within/ beheld wel Robyn Hode” [all who were ever within the church/ beheld Robin Hood well] (73-74). By the time he starts fighting and killing, it’s because he’s surrounded, and he can’t save himself from imprisonment regardless. It may be an impressive show of prowess, but his solitary sword breaks and leaves him without recourse. The very fact that he could kill and wound so many men indicates the impossible odds he was facing. Unlike John’s more subtle tactics, Robin chooses to enter the scene as himself and ends up playing a desperate defense. It is not surprising that Robin chooses this moment to announce, “Alas, alas! ... Now mysse I Litull John” ['Alas, alas! ... Now I miss Little John'] (101-102). Separation from Little John and the kind of behavior and thinking that Little John represents leads Robin straight to a dungeon. And it is only Little John’s bold trickery that can bring him back to the forest.

Little John, on the other hand, delights in tricking and playacting. He and Much have the monk convinced that they’re fellow travelers, innocent men with a shared fear of Robin’s gang. They approach the monk and page “[a]s curtes men and hende” [as courteous and gracious men] while commiserating with the monk over Robin Hood’s murderous crew of “many a wilde felow” [many a wild fellow] (160; 179). Because Little John's identity as an outlaw is so clear to him, because Sherwood is in his very being, he can take on new personas as he pleases. He has freedom of movement and role precisely because he is inextricably bound to the greenwood and to his place as outlaw there. He and Much act the part of friendly, courteous men while contrasting their own behavior with that of the wild outlaws, but they are far more dangerous in their amicable guise than they would be in their own outlaw roles. Where Robin walks into church as himself and raises immediate suspicion, Little John aligns himself with the monk even as he plays upon the monk’s fears of outlaw attack. John can win such games easily because non-outlaws don’t even know they’re playing. His confident playfulness allows him to overcome his opponents time and again, employing such subtle offense that the defense never enters the field. The only moment of the ballad in which Little John reveals his identity to those he's tricked is in fact the moment in which he beheads the monk. The ballad explains that,

The munke saw he shulde be ded,

Lowd mercy can he crye.

'He was my maister,' seid Litull John,

'That thou hase browght in bale;

Shalle thou never cum at oure kyng,

For to telle hym tale.' (197-202)

[The monk saw he should be dead,

Loud mercy he did cry.

'He was my master,' said Little John,

'That you have brought to harm;

You shall never come to our king,

In order to tell him the tale.']

The beheading isn't instantaneous; John gives the monk time to see his imminent peril and cry mercy, and the outlaw responds to the cry for mercy with his own identity as Robin's man and with his reasons for killing the monk—apparently a blend of vengeance and expediency. In this way, Little John makes utterly clear that his playacting is always within the context of his true role as an outlaw of Robin's band.

|

| Charlotte Harding image (1903) courtesy of the Robin Hood Project |

The moment in which Little John beheads the monk and Much beheads the little page has managed to lodge itself firmly in readers' minds, a horrifying scene emblematic of the violent nature of these early ballads. Derek Pearsall writes in "Little John and the ballad of Robin Hood and the Monk" (In Robin Hood: Medieval and Post-Medieval. Ed. Helen Phillips. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2005. Pp. 42-50) that the murder of the little page “is the truly shocking moment of the ballad” and goes on to say that the episode serves to remind us “of a world of brutal and unsentimental saga-heroes in which decency, a respect for the lives of the innocent, what we usually call a sense of honor and fair play, are not part of the code of behavior in the way we might expect” (46). It is true that this is a brutal and unsentimental scene, that the beheading of a child is simply a smart cautionary move to these men, but this is not straightforward violence. Brutal it may be, but it is couched in play and trickery, and those very traits are part of a different kind of code. The scene of clever trickery and dramatic irony could be funny or cute if it didn’t lead to a double execution. (It occurs to me that an alternate title for my paper could have been "It’s all fun and games until someone gets beheaded" ... ) What really makes the incident so shocking is not just the violence, but that the violence exists in a ballad filled with such joyful language and during a scene of such playful disguise. The ballad lulls the reader even as Little John lulls the monk.

Once John and Much exact their revenge on monk and page, the stakes of Little John’s trickery grow higher with each scene. Initially he just impersonates a friendly traveler, a courteous fellow. But then he has the monk’s letters and takes on the role of emissary from the sheriff. The letters functions as tangible proof of his assumed role, and they gives him direct access to not just the court but to the king’s person. The king responds with trust, providing John and Much with a twenty pound reward, making them “yemen of the crown,” and giving Little John the royal seal (229). His dangerous game thus leads directly to a promotion in class from the king himself. Carrying the royal seal is not to impersonate the king, but it is to impersonate the king’s messenger, to claim that your words are his. At every stage, John more boldly uses his words to trick, and his tricks increasingly give him access to information and spaces that would otherwise have been unavailable to him. As the letters ushered him into the king’s company, the seal renders the boundaries of both city and prison permeable to him. Whereas Robin’s overbold actions lead to imprisonment, John’s brand of boldness breaks through prison walls. John is no less violent, no less willing to kill and wound, but he does so with a spirited playfulness that Robin never manages in this ballad. The king may get the final word in the ballad, but he only admits that Little John has won the game: "'Speke no more of this mater,' seid oure kyng,/ 'But John has begyled us alle'" ['Speak no more of this matter,' said our king,/ 'But John has beguiled us all'] (353-354). Focusing on John's success in beguiling everyone rather than on the murders committed along the way, the king's final words sum up the ballad's interest in John's trickery above the moments of violence.

|

| "As light as lef on lynde" |

The outlaws, for their part, aren't phased by the high death count. When Robin escapes jail and returns to the greenwood, the ballad explains that he is "[a]s light as lef on lynde" [as carefree as a leaf on a tree], connecting his joy at returning to the greenwood with the very leaf imagery associated with that space (302). He's a part of the green world again in a way that he wasn't at the beginning of the ballad, when he interrupted the merry tone with his worries about attending mass. His freedom is both stemming from the natural world and bound to it. His very lightness is not just like a leaf, but like a leaf on a tree, linked to the greenwood at its very core. The opposite of being locked in "depe prison," the ballad indicates, is the tenuous and yet stable bond that links foliage to branch and branch to root and root to the larger network of the forest (246). Freedom of movement thus comes with a kind of stability associated with certainty of place, with rootedness. John's playful violence can exist because, connected as he is to the greenwood and his position in it, he can move in and out of forest and in and out of his outlaw role. Identity is thus fluid only to the extent it is fixed.

Little John's outward identity is as malleable as his physical location; he can deceive and playact and win games only he knows are being played. The ballad, which combines beautiful and joyful natural imagery with startling violence, in fact presents us with a world in which the two are mutually constitutive. Dangerous and even deadly play must be used in order to maintain the outlaw condition. In The Forest of Medieval Romance (Cambridge, England; Rochester, NY, USA: D.S. Brewer, 1993), Corinne Saunders describes the greenwood of the Robin Hood ballads as a place where “it is always spring, and where merriment and plenitude of dear dominate. In the ballads, the threats and oppositions are caused not by the difficulties of the life in the greenwood, but by the problematic nature of the position of the outlaw and the occasional reminders of a harsher society whose laws do not look favorably upon such as Robin Hood” (200). While the greenwood of Robin Hood and the Monk is certainly, as Saunders describes, a springtime world of merriment, it seems to me that this ballad complicates the simple opposition between greenwood and town. It is not simply a tale that contrasts the peace and freedom of the greenwood with the oppression of the town, but a ballad in which the very peace and freedom provided by the natural space of the forest is predicated upon a specific kind of violence. Playful acts of violence come naturally to Little John, and Little John in turn is a representative of the greenwood. Little John speaks a language of birdsong and sunlight and green leaves, and he lies and kills as easily as he breathes. The paths of Sherwood make up the cartography of his brain, and with that knowledge he infiltrates court and town and prison. He brings the rules (or lack thereof) of the greenwood with him where he goes, and through them he returns Robin Hood to the forest. He might not have been able to cheer Robin up at the ballad's opening, but he can ultimately render Robin leaf-like and free. As this freedom, like a leaf, is imagined to be affixed to a tree, so is the link to the greenwood essential for Robin and his merry men. Their merriness thrives insofar as their identities remain tied to the forest where they make their home.