Last summer I spent an idyllic weekend at Cape Cod with my close friends, Audrey, Ali, and Hilarie. Audrey's parents graciously hosted us at their lovely home. We enjoyed delicious sea food meals cooked by Audrey's mother, spent quiet moments of reading and yoga in the sunlight-filled backyard, explored the main streets of local towns, and splashed and played in the waters of the beaches. Remembering these moments of peace and excitement and friendship has sustained me through a hectic year. I'd never been to Cape Cod before, and I thoroughly enjoyed exploring the area. I also felt relieved to be near the ocean again. Having spent my whole life within an easy drive from the beach, living in Rochester has been an adjustment for me. Sure, the beaches of Lake Ontario are close by, but a lake is not the ocean, no matter how great it is. (And I feel like the area is taunting me by naming everything around Lake Ontario "Sea Breeze.") During our trip, we went on a whale watching excursion one evening, and were surprised and awed by the whales we saw. Our timing must have been right, because the whales were surrounding our boat, leaping and eating and waving their fins at us.

The naturalist on board counted around 50 whales, and said he'd never seen anything like it. I could not have predicted how delighted I was as these whales emerged from the watery depths. And I was not alone. All around the deck I heard gasps of excitement and joy. Perfect strangers were smiling at each other, exchanging gleeful words, and even high-fiving and hugging. A diverse group of people who had never seen each other before, we were suddenly bonded by our experience with these creatures. We forgot polite distances and social codes of behavior in the face of something so massive. Whales do not come from our world. They are of the water. And yet they're mammals. They can visit us and they can breath in our realm.

As I was watching these humpbacks feed and play, it occurred to me that my reaction (indeed the reactions of everyone on board) was based upon our society's views about (and knowledge of) whales. If we had no understanding of these creatures, if we didn't grow up singing "Baby Beluga" and visiting marine parks, our little excursion would have produced a very different response. Instead of being overjoyed by the experience, we would have been terrified. Glimpses of fin and tail in the water could be easily mistaken for a sea monster. These whales, if they had wanted to, could have overturned our boat with ease. I was reminded of the Anglo-Saxon poem about the whale from the Exeter Book in which the whale is described as a fierce creature that terrifies seafarers.

In an image worthy of a Loony Toons cartoon, the poem describes how sailers sometimes mistake the whale's back for an island. Then the poem takes an eerie turn as the whale waits until the sailers are settled and comfortable on his back only to dive deep and drown them. The whale, we are told, is like the devil, who fools us with earthly pleasures only to draw us down to hell. This poem of insular uncertainty, in which the land we seek may really be part of the water, bears little resemblance to our experience of whales today. But it's not unreasonable to fear these massive water-dwellers if we know nothing of them. The ocean is unimaginably vast; its depths are beyond human exploration. Because we cannot know what lies below the waters, because we are never sure what's lurking beneath us, the ocean is a kind of mysterious wilderness zone. Majestic and beautiful, yes, but a little frightening too. We had faith in the benevolence of the whales we saw that day, and I suppose they had faith in our benevolence as well. Two worlds met for a brief moment, and we were changed because of it.

I attempted to contain this transformational experience with my camera, snapping pictures as quickly as I could and trying to capture the fleeting moments of fin and tail. As hard as I tried, I couldn't fit the larger-than-life adventure through my camera lens. I was reminded of Jeffrey Jerome Cohen's discussion of the body in pieces from his book Of Giants. He explains that, "[w]hen placed inside a human frame of reference, the giant can be known only through synecdoche: a hand that grasps, a lake that has filled his footprint, a shoe or glove that dwarfs the human body by its side. To gaze on the giant as more than a body in pieces requires the adoption of an inhuman, transcendent point of view; yet beside the full form of the giant, the human body dwindles to a featureless outline, like those charts in museums that depict a tiny silhouette of Homo sapiens below a fully realized Tyrannosaurus rex" (xiii).

Cohen was surely inspired in part by Susan Stewart's On Longing, which states that "we know the gigantic only partially" (71). Like the giant, the whale is larger than our eyes can fix upon at any one moment. But even beyond that, only pieces of the whale ever emerge from the water at a time. And the camera can catch only miniaturized glimpses of these pieces. The ocean, too, is only available to us in pieces. We can paint blue onto an atlas or globe, but the ocean in its vastness can only be experienced a little at a time: a stretch of beach, an expanse of waves, a bit of horizontal line in which salty green-blue defines itself against azure sky.

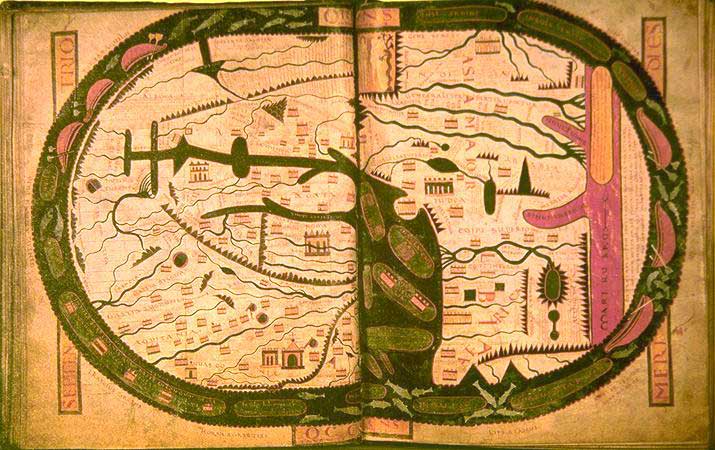

The ocean is an overwhelming presence in the world, surrounding and overlapping the land. To conceptualize it, we must shrink it down. Yet medieval British cartographers took this shrinkage to the extreme, depicting the world with decidedly little water. Medieval mappae mundi were aesthetic and ideological creations. They were images of the world that gave a worldview; they might help you find your place in a spiritual or metaphorical sense, but would be of little service planning a road trip. (See my previous posts on maps here and here.) On these world maps, the further you get from the center, the stranger things become. Yet the ocean in these maps is more marginal than even the monsters, a blank ring around the edge of the world, a circle which bounds and shapes the earth and yet is separate from it. The landed realms in these maps are encyclopedic, covered in the text of biblical and classical and contemporary history. They indicate the connections between topographical features and the historical events that occurred there. The ocean, on the other hand, is a blank ring around that visual-textual landscape.

I would caution that the depiction of the ocean in such maps is not due to ignorance -- mapmakers were certainly aware of the vast watery realm that covers much of the earth -- but instead because the water was not integral to the aims of these maps. The land is the space of history. Humans mark the topography on land and specific locations and events can be recorded. Land is the realm of humankind. The ocean is not our realm. We may float or we may sink, but we are always out of our element when in the water.

Yet the land and sea merge and overlap in unsettling and beautiful ways. The waves push and pull at the shore. Tides go in and out, marking the cycles of day and season even as they shift the boundary between land and water. And under the deepest ocean the sea floor can be found. Islands, too, indicate an uncomfortable land to sea ratio. The ocean surrounds islands as it surrounds mappae mundi, and we can only hope that we're on solid ground instead of on the back of a stealthy creature of the deep.