I was recently talking with my wonderful dissertation group, consisting of Kara McShane and Laura Bell, about traveling. Though we are all three writing about different texts (and Laura is writing about nineteenth-century literature, whereas Kara and I do medieval), all of us are dealing with travel in some way. We were thinking the other day about how frequently we answer distance questions with time. "How far is it to your apartment?" "About ten minutes." We very often measure length of distance with how long it will take to traverse it. We measure distance in minutes, in hours, in days. "A day's drive" can mean different things on different days and for different people, but we all understand that it means the limit of how far a person could travel on a given day. All of this got me thinking about the word "journey," which clearly has its origins in the French jour – day. A journey, then, is how far you could get in a day, the pre-modern equivalent of a day's drive. Before speedometers and gps systems and google maps, how would you tell someone how far to travel? How would you orient yourself on a trip? How would you negotiate between spaces?

As a Californian, the most tangible experience I have of day's travel is of learning about the missions that dot the expanse of the state. As a history-loving child in a fairly new state, the missions were exciting to visit when I was growing up because they were some of the oldest buildings around. Through them, I had a tangible connection to the way that cultural and historical change had occurred in my state. I made a model of the San Carlos Borromeo Carmelo Mission in fourth grade for school, and I poured over the history, architecture, landscape of that mission. I was so proud of my model because my dad helped me cut the top layer from cardboard and then paint the wavy part of the board red to create the roof tiles of the building. This was, for me, a crowning achievement of my elementary school career. What I couldn't replicate, however, was the geographical and temporal connection between my mission and the rest of the missions. An isolated model of a mission, or even an isolated visit to one mission, misses the larger network of the 21 missions that run up the Pacific coast. The missions are all a day's horse ride apart, since the Spanish missionaries would ride a full day and then stop to build another one. The distance between these buildings, then, is not one of miles but one of time travelled. Length as time is literally written onto the landscape in California. The Spanish missionaries colonized and converted the Pacific coast one day's ride at a time. By building actual edifices to mark the journeys and by planting European crops around these missions, the colonializing progress up the coast alters the landscape as well as the culture of the region. Missionaries marked their day-long movements with adobe and timber and stone, and each building also served as a locus for the spread of Spanish language and religion and culture and flora and fauna.

The missions are interesting for my thoughts on distance as time because they represent a larger teleology, both of linear progress up the coast and of the colonization and conversion of the locals, and yet each point on the line of missions is of equal importance. It's not about making it to the northernmost or southernmost mission, but rather about the presence of missions along the whole length of the state. It is, to give into the inevitable cliche, about both journey and destination. Perhaps the answer is that there's a larger movement up the coast, but yet each mission also represents its own destination. The line is made up of individual journeys. And though we no longer ride horses to get from one spot to another (or, rather, I never have), we still think of movement across the state or country or world in terms of segments of travel.

When we answer distance questions with time we collapse time and space. But often such a collapse serves a particularly teleological way of thinking. I answer that it takes ten minutes to reach my apartment because I assume that you plan to go from point A, here, to point B, there. What happens, then, when there is no destination in mind, when we know neither point A nor point B? This, as anyone who knows me might have guessed already, leads me back to the idea of rudderless ships. In the ocean, when the directions one could travel are endless and when no point can be permanently marked as A or B or anything else, how can we conceive of a journey? With no oars, with no sail, with no observable landmarks, distance is unmeasurable. And perhaps, on a journey, unmeasurable distance leads to unmeasurable time. Perhaps this is why, as I have mentioned before, Custance travels for "years and days" in the Man of Law's Tale. We don't get specifics about time (how many years? how many days?) because neither time nor space nor the connection between them is clear on a rudderless voyage. Custance doesn't know how far she travels, how long she's at sea, or where she's heading. Her boat floats in all directions for some amount of time. Fate has a larger plan for her, as the Man of Law makes clear, but fate isn't quantifiable, and thus can't be productively measured in time or space. I guess, if you don't know where you're going, you really have no choice but to focus on the journey.

Showing posts with label sea. Show all posts

Showing posts with label sea. Show all posts

Saturday, November 3, 2012

How do you get from A to B if you have no alphabet?

Labels:

California,

Canterbury tales,

Chaucer,

Constance-Cycle,

Custance,

destination,

dissertation,

distance,

geography,

journey,

Man of Law's Tale,

medieval,

mission,

missionary,

ocean,

road trip,

sea,

topography,

travel

Sunday, August 26, 2012

One foot in the sea and the other on land

As I transition from one coast to another, one school year to another, and one season to another, I think a lot about thresholds. I try hard to think of each phase or moment or experience in my life as a thing unto itself instead of a place between. Graduate school, for example, could be a liminal space between college and career, but it seems a shame to think of such an extended period of my life as simply a means to an end (especially in this uncertain market). Sometimes I sit in a coffee shop, reading or writing, and I really reflect on how privileged I am to be able to spend some years of my life learning and thinking and growing as a person and a scholar. How amazing it is to sit in the afternoon sunlight, reading a book and learning even more about the things I love. How incredible it is to work with students and to see them really think about literature and the world around them. Even the struggle to come up with new ideas, the intensity of teaching, the insecurities which come with grad school -- those are a part of my life, a part of all that's good in it and all that makes it worthwhile to me. These years, I must remind myself, are valuable unto themselves.

As a medievalist, the struggle against the idea of middles is constant. Though the term "Middle Ages" is certainly less pejorative than "Dark Ages," it still gives a sense of a period between the glory of Rome and the Renaissance. A placeholder in history. It seems doubtful to me that people woke up on New Year's Day of 1500 (or 1495 or 1450 or 1350 or 1300 …) and felt suddenly reborn. Even midnight on New Year's, which seems to be a crystal-clear liminal point, shatters when we consider all of the time zones of the world. Watching through a television set in the United States as the ball drops in Australia, I can't help but feel a bit unsettled about our privileging of that particular moment. Nor can I fail to notice when I reach the new year in New York before my friends in California do. And this is not to mention the fact that there are different calendars in the world that have different New Year's, and the fact that even our Gregorian calendar has been used with different New Year's in mind. In the Middle Ages there seem to have been several possible dates, and people in the Early Modern period celebrated on March 25th. How are we to find the point of transition if it keeps moving? And what do we do with a transition period, a middle, that takes up a thousand years? It's interesting that we often think of middle as center, as central. We often see those things on the periphery as less important. Yet in history as in our lives it's easy to see moments or years or centuries as simply between the real thing. Not only does this kind of thinking ignore realities of connection and continuity, but it denies the importance of the individual dots on the timeline.

On my trip home I spent some nice afternoons at the beach, visiting my much-missed Pacific Ocean, and I thought about how hard it often is to pinpoint a precise spot where one time or space ends and another begins. I walked through that tricky line on the shore where dry feet and wet feet are only moments apart, and I examined that strip of sand. What was above water one moment was below it the next, and even the extent to which the water reached was always different. The curved border between dry sand and wet sand (and even wetter sand) shifts constantly, and must be slightly different each day. Indeed, it must change throughout the day as well, and in more subtle ways than just the changing tides. As I rolled up my jeans and moved closer to the water, I noticed that the way the water moves over the sand is new each time, that the ripples of water are ever-changing and that they leave an imprint both of their shape and their substance on the sand behind them. As I tried to discern the line between the realms of ocean and sea, I found that there really is no simple answer. There is no line and there's always a line and there are a million different lines. I spoke in my paper at the recent NCS conference on the Man of Law's Tale about how the realms of land and sea are never as separate as they appear on the map, and it was good to actually look at the space between and in those realms. So often I find myself getting caught up in the theoretical. Of course I am a literature person -- examining texts is what I do. And I'm a medievalist -- thinking about things long ago is my job. But after writing so much about concepts of time and space and the ocean, it's good to get reacquainted with the ocean itself. To get my feet wet again, as it were.

On my trip I was reading Rachel Carson's The Sea Around Us, and was struck by a passage from the preface to the 1961 edition describing how the floor of the deep sea "receives[s] sediments from the margins of the continents" such as "bits of wood and leaves, and … sands containing nuts, twigs, and the bark of trees" (x).The abyssal plains, therefore, include tangible pieces of the coast. And it is also the waters of the world that have carved out valleys and canyons now well above ground. Water has in many ways shaped our landscapes, just as the land provides the floor of our oceans and rivers. Carson explains of the ocean's formation that water wore away the land to create the ocean, while the minerals from these worn-away continents gave the sea its saltiness in "an endless, inexorable process that has never stopped" (7). In other words, the water continually shapes the land, while the land ceaselessly gives the ocean its salty form. Over the long history of the earth, land and sea have merged, shifted, and forged one another. Geological time, it seems, has its own ideas about topographical and temporal boundaries. To try to think of any particular space or time as its own separate entity really only works in a single instant. Even in that instant the lines are fraught, but only in that instant are lines really visible. Boundaries and borders are shifting, fleeting, intersecting. I played with this notion by snapping pictures of the space where ocean meets shore in order to try to capture some of those threshold moments. And even in my photographs, I cannot really tell for sure where water ends and sand begins. Can you?

As a medievalist, the struggle against the idea of middles is constant. Though the term "Middle Ages" is certainly less pejorative than "Dark Ages," it still gives a sense of a period between the glory of Rome and the Renaissance. A placeholder in history. It seems doubtful to me that people woke up on New Year's Day of 1500 (or 1495 or 1450 or 1350 or 1300 …) and felt suddenly reborn. Even midnight on New Year's, which seems to be a crystal-clear liminal point, shatters when we consider all of the time zones of the world. Watching through a television set in the United States as the ball drops in Australia, I can't help but feel a bit unsettled about our privileging of that particular moment. Nor can I fail to notice when I reach the new year in New York before my friends in California do. And this is not to mention the fact that there are different calendars in the world that have different New Year's, and the fact that even our Gregorian calendar has been used with different New Year's in mind. In the Middle Ages there seem to have been several possible dates, and people in the Early Modern period celebrated on March 25th. How are we to find the point of transition if it keeps moving? And what do we do with a transition period, a middle, that takes up a thousand years? It's interesting that we often think of middle as center, as central. We often see those things on the periphery as less important. Yet in history as in our lives it's easy to see moments or years or centuries as simply between the real thing. Not only does this kind of thinking ignore realities of connection and continuity, but it denies the importance of the individual dots on the timeline.

On my trip home I spent some nice afternoons at the beach, visiting my much-missed Pacific Ocean, and I thought about how hard it often is to pinpoint a precise spot where one time or space ends and another begins. I walked through that tricky line on the shore where dry feet and wet feet are only moments apart, and I examined that strip of sand. What was above water one moment was below it the next, and even the extent to which the water reached was always different. The curved border between dry sand and wet sand (and even wetter sand) shifts constantly, and must be slightly different each day. Indeed, it must change throughout the day as well, and in more subtle ways than just the changing tides. As I rolled up my jeans and moved closer to the water, I noticed that the way the water moves over the sand is new each time, that the ripples of water are ever-changing and that they leave an imprint both of their shape and their substance on the sand behind them. As I tried to discern the line between the realms of ocean and sea, I found that there really is no simple answer. There is no line and there's always a line and there are a million different lines. I spoke in my paper at the recent NCS conference on the Man of Law's Tale about how the realms of land and sea are never as separate as they appear on the map, and it was good to actually look at the space between and in those realms. So often I find myself getting caught up in the theoretical. Of course I am a literature person -- examining texts is what I do. And I'm a medievalist -- thinking about things long ago is my job. But after writing so much about concepts of time and space and the ocean, it's good to get reacquainted with the ocean itself. To get my feet wet again, as it were.

On my trip I was reading Rachel Carson's The Sea Around Us, and was struck by a passage from the preface to the 1961 edition describing how the floor of the deep sea "receives[s] sediments from the margins of the continents" such as "bits of wood and leaves, and … sands containing nuts, twigs, and the bark of trees" (x).The abyssal plains, therefore, include tangible pieces of the coast. And it is also the waters of the world that have carved out valleys and canyons now well above ground. Water has in many ways shaped our landscapes, just as the land provides the floor of our oceans and rivers. Carson explains of the ocean's formation that water wore away the land to create the ocean, while the minerals from these worn-away continents gave the sea its saltiness in "an endless, inexorable process that has never stopped" (7). In other words, the water continually shapes the land, while the land ceaselessly gives the ocean its salty form. Over the long history of the earth, land and sea have merged, shifted, and forged one another. Geological time, it seems, has its own ideas about topographical and temporal boundaries. To try to think of any particular space or time as its own separate entity really only works in a single instant. Even in that instant the lines are fraught, but only in that instant are lines really visible. Boundaries and borders are shifting, fleeting, intersecting. I played with this notion by snapping pictures of the space where ocean meets shore in order to try to capture some of those threshold moments. And even in my photographs, I cannot really tell for sure where water ends and sand begins. Can you?

Labels:

Carson,

Chaucer,

conference,

Constance-Cycle,

Custance,

Grad school,

history,

liminal,

Man of Law's Tale,

medieval,

Middle Ages,

middles,

NCS,

New Chaucer Society,

ocean,

sea,

teaching,

timeline,

transition

Wednesday, May 2, 2012

The Whale and the Deep Blue Sea: Standing Ashore and Imagining OceanSpaces

Last summer I spent an idyllic weekend at Cape Cod with my close friends, Audrey, Ali, and Hilarie. Audrey's parents graciously hosted us at their lovely home. We enjoyed delicious sea food meals cooked by Audrey's mother, spent quiet moments of reading and yoga in the sunlight-filled backyard, explored the main streets of local towns, and splashed and played in the waters of the beaches. Remembering these moments of peace and excitement and friendship has sustained me through a hectic year. I'd never been to Cape Cod before, and I thoroughly enjoyed exploring the area. I also felt relieved to be near the ocean again. Having spent my whole life within an easy drive from the beach, living in Rochester has been an adjustment for me. Sure, the beaches of Lake Ontario are close by, but a lake is not the ocean, no matter how great it is. (And I feel like the area is taunting me by naming everything around Lake Ontario "Sea Breeze.") During our trip, we went on a whale watching excursion one evening, and were surprised and awed by the whales we saw. Our timing must have been right, because the whales were surrounding our boat, leaping and eating and waving their fins at us.

The naturalist on board counted around 50 whales, and said he'd never seen anything like it. I could not have predicted how delighted I was as these whales emerged from the watery depths. And I was not alone. All around the deck I heard gasps of excitement and joy. Perfect strangers were smiling at each other, exchanging gleeful words, and even high-fiving and hugging. A diverse group of people who had never seen each other before, we were suddenly bonded by our experience with these creatures. We forgot polite distances and social codes of behavior in the face of something so massive. Whales do not come from our world. They are of the water. And yet they're mammals. They can visit us and they can breath in our realm.

As I was watching these humpbacks feed and play, it occurred to me that my reaction (indeed the reactions of everyone on board) was based upon our society's views about (and knowledge of) whales. If we had no understanding of these creatures, if we didn't grow up singing "Baby Beluga" and visiting marine parks, our little excursion would have produced a very different response. Instead of being overjoyed by the experience, we would have been terrified. Glimpses of fin and tail in the water could be easily mistaken for a sea monster. These whales, if they had wanted to, could have overturned our boat with ease. I was reminded of the Anglo-Saxon poem about the whale from the Exeter Book in which the whale is described as a fierce creature that terrifies seafarers.

In an image worthy of a Loony Toons cartoon, the poem describes how sailers sometimes mistake the whale's back for an island. Then the poem takes an eerie turn as the whale waits until the sailers are settled and comfortable on his back only to dive deep and drown them. The whale, we are told, is like the devil, who fools us with earthly pleasures only to draw us down to hell. This poem of insular uncertainty, in which the land we seek may really be part of the water, bears little resemblance to our experience of whales today. But it's not unreasonable to fear these massive water-dwellers if we know nothing of them. The ocean is unimaginably vast; its depths are beyond human exploration. Because we cannot know what lies below the waters, because we are never sure what's lurking beneath us, the ocean is a kind of mysterious wilderness zone. Majestic and beautiful, yes, but a little frightening too. We had faith in the benevolence of the whales we saw that day, and I suppose they had faith in our benevolence as well. Two worlds met for a brief moment, and we were changed because of it.

I attempted to contain this transformational experience with my camera, snapping pictures as quickly as I could and trying to capture the fleeting moments of fin and tail. As hard as I tried, I couldn't fit the larger-than-life adventure through my camera lens. I was reminded of Jeffrey Jerome Cohen's discussion of the body in pieces from his book Of Giants. He explains that, "[w]hen placed inside a human frame of reference, the giant can be known only through synecdoche: a hand that grasps, a lake that has filled his footprint, a shoe or glove that dwarfs the human body by its side. To gaze on the giant as more than a body in pieces requires the adoption of an inhuman, transcendent point of view; yet beside the full form of the giant, the human body dwindles to a featureless outline, like those charts in museums that depict a tiny silhouette of Homo sapiens below a fully realized Tyrannosaurus rex" (xiii).

Cohen was surely inspired in part by Susan Stewart's On Longing, which states that "we know the gigantic only partially" (71). Like the giant, the whale is larger than our eyes can fix upon at any one moment. But even beyond that, only pieces of the whale ever emerge from the water at a time. And the camera can catch only miniaturized glimpses of these pieces. The ocean, too, is only available to us in pieces. We can paint blue onto an atlas or globe, but the ocean in its vastness can only be experienced a little at a time: a stretch of beach, an expanse of waves, a bit of horizontal line in which salty green-blue defines itself against azure sky.

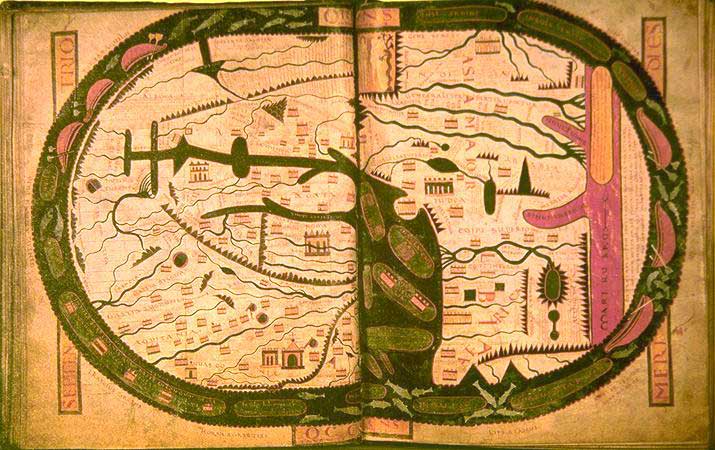

The ocean is an overwhelming presence in the world, surrounding and overlapping the land. To conceptualize it, we must shrink it down. Yet medieval British cartographers took this shrinkage to the extreme, depicting the world with decidedly little water. Medieval mappae mundi were aesthetic and ideological creations. They were images of the world that gave a worldview; they might help you find your place in a spiritual or metaphorical sense, but would be of little service planning a road trip. (See my previous posts on maps here and here.) On these world maps, the further you get from the center, the stranger things become. Yet the ocean in these maps is more marginal than even the monsters, a blank ring around the edge of the world, a circle which bounds and shapes the earth and yet is separate from it. The landed realms in these maps are encyclopedic, covered in the text of biblical and classical and contemporary history. They indicate the connections between topographical features and the historical events that occurred there. The ocean, on the other hand, is a blank ring around that visual-textual landscape.

I would caution that the depiction of the ocean in such maps is not due to ignorance -- mapmakers were certainly aware of the vast watery realm that covers much of the earth -- but instead because the water was not integral to the aims of these maps. The land is the space of history. Humans mark the topography on land and specific locations and events can be recorded. Land is the realm of humankind. The ocean is not our realm. We may float or we may sink, but we are always out of our element when in the water.

Yet the land and sea merge and overlap in unsettling and beautiful ways. The waves push and pull at the shore. Tides go in and out, marking the cycles of day and season even as they shift the boundary between land and water. And under the deepest ocean the sea floor can be found. Islands, too, indicate an uncomfortable land to sea ratio. The ocean surrounds islands as it surrounds mappae mundi, and we can only hope that we're on solid ground instead of on the back of a stealthy creature of the deep.

The naturalist on board counted around 50 whales, and said he'd never seen anything like it. I could not have predicted how delighted I was as these whales emerged from the watery depths. And I was not alone. All around the deck I heard gasps of excitement and joy. Perfect strangers were smiling at each other, exchanging gleeful words, and even high-fiving and hugging. A diverse group of people who had never seen each other before, we were suddenly bonded by our experience with these creatures. We forgot polite distances and social codes of behavior in the face of something so massive. Whales do not come from our world. They are of the water. And yet they're mammals. They can visit us and they can breath in our realm.

As I was watching these humpbacks feed and play, it occurred to me that my reaction (indeed the reactions of everyone on board) was based upon our society's views about (and knowledge of) whales. If we had no understanding of these creatures, if we didn't grow up singing "Baby Beluga" and visiting marine parks, our little excursion would have produced a very different response. Instead of being overjoyed by the experience, we would have been terrified. Glimpses of fin and tail in the water could be easily mistaken for a sea monster. These whales, if they had wanted to, could have overturned our boat with ease. I was reminded of the Anglo-Saxon poem about the whale from the Exeter Book in which the whale is described as a fierce creature that terrifies seafarers.

In an image worthy of a Loony Toons cartoon, the poem describes how sailers sometimes mistake the whale's back for an island. Then the poem takes an eerie turn as the whale waits until the sailers are settled and comfortable on his back only to dive deep and drown them. The whale, we are told, is like the devil, who fools us with earthly pleasures only to draw us down to hell. This poem of insular uncertainty, in which the land we seek may really be part of the water, bears little resemblance to our experience of whales today. But it's not unreasonable to fear these massive water-dwellers if we know nothing of them. The ocean is unimaginably vast; its depths are beyond human exploration. Because we cannot know what lies below the waters, because we are never sure what's lurking beneath us, the ocean is a kind of mysterious wilderness zone. Majestic and beautiful, yes, but a little frightening too. We had faith in the benevolence of the whales we saw that day, and I suppose they had faith in our benevolence as well. Two worlds met for a brief moment, and we were changed because of it.

I attempted to contain this transformational experience with my camera, snapping pictures as quickly as I could and trying to capture the fleeting moments of fin and tail. As hard as I tried, I couldn't fit the larger-than-life adventure through my camera lens. I was reminded of Jeffrey Jerome Cohen's discussion of the body in pieces from his book Of Giants. He explains that, "[w]hen placed inside a human frame of reference, the giant can be known only through synecdoche: a hand that grasps, a lake that has filled his footprint, a shoe or glove that dwarfs the human body by its side. To gaze on the giant as more than a body in pieces requires the adoption of an inhuman, transcendent point of view; yet beside the full form of the giant, the human body dwindles to a featureless outline, like those charts in museums that depict a tiny silhouette of Homo sapiens below a fully realized Tyrannosaurus rex" (xiii).

Cohen was surely inspired in part by Susan Stewart's On Longing, which states that "we know the gigantic only partially" (71). Like the giant, the whale is larger than our eyes can fix upon at any one moment. But even beyond that, only pieces of the whale ever emerge from the water at a time. And the camera can catch only miniaturized glimpses of these pieces. The ocean, too, is only available to us in pieces. We can paint blue onto an atlas or globe, but the ocean in its vastness can only be experienced a little at a time: a stretch of beach, an expanse of waves, a bit of horizontal line in which salty green-blue defines itself against azure sky.

The ocean is an overwhelming presence in the world, surrounding and overlapping the land. To conceptualize it, we must shrink it down. Yet medieval British cartographers took this shrinkage to the extreme, depicting the world with decidedly little water. Medieval mappae mundi were aesthetic and ideological creations. They were images of the world that gave a worldview; they might help you find your place in a spiritual or metaphorical sense, but would be of little service planning a road trip. (See my previous posts on maps here and here.) On these world maps, the further you get from the center, the stranger things become. Yet the ocean in these maps is more marginal than even the monsters, a blank ring around the edge of the world, a circle which bounds and shapes the earth and yet is separate from it. The landed realms in these maps are encyclopedic, covered in the text of biblical and classical and contemporary history. They indicate the connections between topographical features and the historical events that occurred there. The ocean, on the other hand, is a blank ring around that visual-textual landscape.

I would caution that the depiction of the ocean in such maps is not due to ignorance -- mapmakers were certainly aware of the vast watery realm that covers much of the earth -- but instead because the water was not integral to the aims of these maps. The land is the space of history. Humans mark the topography on land and specific locations and events can be recorded. Land is the realm of humankind. The ocean is not our realm. We may float or we may sink, but we are always out of our element when in the water.

Yet the land and sea merge and overlap in unsettling and beautiful ways. The waves push and pull at the shore. Tides go in and out, marking the cycles of day and season even as they shift the boundary between land and water. And under the deepest ocean the sea floor can be found. Islands, too, indicate an uncomfortable land to sea ratio. The ocean surrounds islands as it surrounds mappae mundi, and we can only hope that we're on solid ground instead of on the back of a stealthy creature of the deep.

Labels:

beach,

Cape Cod,

cartography,

Cohen,

geography,

mappa mundi,

medieval,

medieval maps,

narrative,

ocean,

Physiologus,

road trip,

sea,

sea monster,

Stewart,

topography,

whale,

whale watch

Friday, April 27, 2012

Tales of Land and Sea: More on Medieval Mappae Mundi

To continue my earlier post on maps, I thought I would go into some of the details of the mappa mundi. As many of you may know, the basic form for these maps is called the T-O map, since the main structure is a "T" inside an "O." The T and O are formed by water, so that the water bounds and shapes and encloses the land, even though the land takes up most of the space and is the focus of the map. The T is the Rivers -- the Mediterranean, the Nile, and the Tanais (i.e. the Don). The O is the ocean, a nameless circle that surrounds the land. The T also separates the continents, with Asia on top, Europe on the bottom left, and Africa on the bottom right. You can see in the above map that each continent is associated with one of Noah's sons: Asia with Sem (Shem), Europe with Iafeth (Japheth), and Africa with Cham (Ham). Jerusalem is at the middle of these maps, where the rivers and continents meet. This location means that Jerusalem was literally the center of the world, the most central and important location available. Move further from that center and things get . . . stranger. On the edges of the map are the so-called monstrous races. Human-like creatures with single feet, or with no heads, or with dog heads, populate the margins of the earth, far from Jerusalem and yet still part of the landed realms. An early (and still very informative) work about the monstrous races is John Bloch Friedman's The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought. There's also much interesting work being done on the placement of Great Britain on these maps, and more still to do. Both Asa Simon Mittman and Kathy Lavezzo have discussed the meaning for England, and English map-makers, that Great Britain is also on the edge of the world in these maps, and I suggest their work to those interested in the topic.

When I teach these maps, I try to get the students to discover the ways in which modern maps are constructed as well. We look at modern maps and discuss the things that aren't directly representative of the geography the maps depict. We talk about those things we've naturalized to the point of thinking they're just true. Since the aspect that surprises the students the most about medieval maps is that Asia is on top, I like to show them an Australian map which flips our normal sense of north as up. I ask why north is on top other than the fact that we've always seen it that way. Who decided? Maybe the fact that compasses point north (for now) had something to do with it, but it still has become the normal depiction to the point that most people think it's somehow natural. The "upside-down map" looks strange, the shapes of the continents unfamiliar, and this defamiliarization is useful for a number of reasons. One is that it helps us to see the geography anew, to attend to the details, since we rarely look as closely at the familiar (like the art assignment where students draw the human face upside-down). Another is that it allows us to think through the implications of the choices the mapmaker has made. What does it mean for north to be on top? What does it mean for Europe to be in the center? What does it mean to choose a projection which contracts and expands different parts of the world? I'm reminded of an episode of West Wing in which "The Organization of Cartographers for Social Equality" take their case to C.J. Cregg. At first, she laughs at the idea of maps having anything to do with social justice. But they show her how different projections alter the image of the earth, and her jaw drops as she realizes that they have a point.

Maybe I'll show that clip next time I teach this material.In any case, looking at different projections and different versions of world maps is a useful exercise, and we're all more ready to discuss the mappae mundi when we return to them. Yes, they're strange, but they're not stupid. And there's nothing inherently wrong with putting east on top. The verb orient comes from the fact that maps were originally oriented to the East (the Orient).

There is much to say about all of this, but I want to focus here on what is barely apparent on the maps: the ocean. Though the ocean forms the "O" and bounds the circle of the land, it nonetheless takes up very little space on the maps. We moderns, used to maps that depict the ocean as more than 70% of the earth's surface, may be surprised to see just how little ocean there is on these medieval world maps. I argue that this is not because medieval mapmakers misunderstood the ocean's vastness, but rather because their maps were ideological, encyclopedic, and aesthetic creations, and the ocean's place around the edges suited these purposes. It left the map symmetrical, but also left the land, and therefore those things that had happened on land, as the primary focus. The land in these maps is covered in classical and biblical and historical details associated with the various spaces on the earth. Humans are at the center of this narrative, and the land is humanity's realm.

There were other kinds of maps for navigating the ocean, and portolan charts helped seafarers from the 13th century on. The fact that mappae mundi and navigational maps were being produced simultaneously indicates that neither was meant to supersede or replace the other; they were simply for different purposes. The mappae mundi did precisely what they were meant to do -- they gave order to geographical and historical and spiritual information. And the land, and all of the things that had happened there in human history, was the focal point. The ocean is an unmarked space surrounding and outside of the land, more marginal indeed than the monsters that populate the edges of the world. The story is on the land, not the ocean, and thus the ocean depicts nothing; it is simply there to gird the earth. Unlike land, the ocean's topography cannot be marked or altered. It's both vast and unaffected (unaffectable) by humans. The contours of the ocean are ever-changing waves. How can you point to a historical location on the shifting contours of the water? How do you make your presence known to later people when you're floating on the sea? Humans may venture out onto the waters of the world in little wooden vessels, but these vessels will either be brought back to harbor or they will sink into the deep. (See my last post on Titanic for more about that.) No man-made contraptions can stay on the ocean's surface, none can leave a trace of human presence except in the depths of the ocean floor, subsumed by the ocean itself.

So the ocean is a blank space on these mappae mundi. It does not partake in the narrative domain of the land, nor does it participate in the historical or ideological aims of the land. It is a realm apart.

When I teach these maps, I try to get the students to discover the ways in which modern maps are constructed as well. We look at modern maps and discuss the things that aren't directly representative of the geography the maps depict. We talk about those things we've naturalized to the point of thinking they're just true. Since the aspect that surprises the students the most about medieval maps is that Asia is on top, I like to show them an Australian map which flips our normal sense of north as up. I ask why north is on top other than the fact that we've always seen it that way. Who decided? Maybe the fact that compasses point north (for now) had something to do with it, but it still has become the normal depiction to the point that most people think it's somehow natural. The "upside-down map" looks strange, the shapes of the continents unfamiliar, and this defamiliarization is useful for a number of reasons. One is that it helps us to see the geography anew, to attend to the details, since we rarely look as closely at the familiar (like the art assignment where students draw the human face upside-down). Another is that it allows us to think through the implications of the choices the mapmaker has made. What does it mean for north to be on top? What does it mean for Europe to be in the center? What does it mean to choose a projection which contracts and expands different parts of the world? I'm reminded of an episode of West Wing in which "The Organization of Cartographers for Social Equality" take their case to C.J. Cregg. At first, she laughs at the idea of maps having anything to do with social justice. But they show her how different projections alter the image of the earth, and her jaw drops as she realizes that they have a point.

Maybe I'll show that clip next time I teach this material.In any case, looking at different projections and different versions of world maps is a useful exercise, and we're all more ready to discuss the mappae mundi when we return to them. Yes, they're strange, but they're not stupid. And there's nothing inherently wrong with putting east on top. The verb orient comes from the fact that maps were originally oriented to the East (the Orient).

There is much to say about all of this, but I want to focus here on what is barely apparent on the maps: the ocean. Though the ocean forms the "O" and bounds the circle of the land, it nonetheless takes up very little space on the maps. We moderns, used to maps that depict the ocean as more than 70% of the earth's surface, may be surprised to see just how little ocean there is on these medieval world maps. I argue that this is not because medieval mapmakers misunderstood the ocean's vastness, but rather because their maps were ideological, encyclopedic, and aesthetic creations, and the ocean's place around the edges suited these purposes. It left the map symmetrical, but also left the land, and therefore those things that had happened on land, as the primary focus. The land in these maps is covered in classical and biblical and historical details associated with the various spaces on the earth. Humans are at the center of this narrative, and the land is humanity's realm.

There were other kinds of maps for navigating the ocean, and portolan charts helped seafarers from the 13th century on. The fact that mappae mundi and navigational maps were being produced simultaneously indicates that neither was meant to supersede or replace the other; they were simply for different purposes. The mappae mundi did precisely what they were meant to do -- they gave order to geographical and historical and spiritual information. And the land, and all of the things that had happened there in human history, was the focal point. The ocean is an unmarked space surrounding and outside of the land, more marginal indeed than the monsters that populate the edges of the world. The story is on the land, not the ocean, and thus the ocean depicts nothing; it is simply there to gird the earth. Unlike land, the ocean's topography cannot be marked or altered. It's both vast and unaffected (unaffectable) by humans. The contours of the ocean are ever-changing waves. How can you point to a historical location on the shifting contours of the water? How do you make your presence known to later people when you're floating on the sea? Humans may venture out onto the waters of the world in little wooden vessels, but these vessels will either be brought back to harbor or they will sink into the deep. (See my last post on Titanic for more about that.) No man-made contraptions can stay on the ocean's surface, none can leave a trace of human presence except in the depths of the ocean floor, subsumed by the ocean itself.

So the ocean is a blank space on these mappae mundi. It does not partake in the narrative domain of the land, nor does it participate in the historical or ideological aims of the land. It is a realm apart.

Labels:

cartography,

Friedman,

geography,

Lavezzo,

mappa mundi,

medieval,

medieval maps,

Middle Ages,

Mittman,

narrative,

ocean,

portolan charts,

sea,

teaching,

topography,

West Wing

Saturday, April 14, 2012

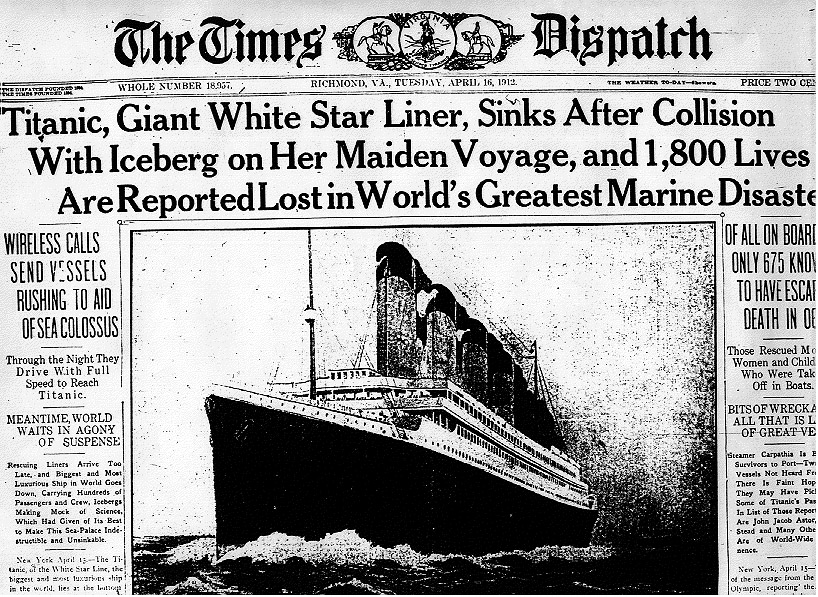

Dredging up the Past: Titanic and the Body of Memory

I just saw Titanic in 3D. I hadn't thought much about going to see it, and had even laughed at this rerelease as an easy money-making endeavor. Yet when some friends asked me to join, I went. I hadn't seen the film since it was in theaters the last time, before it won too many awards and became a parody of itself (i.e. "I'm king of the wooorld!"). I saw it on my first real date, cliche as that may be, and watched it with a mixed response. For the teenaged me, it was sad and awkward and romantic and manipulatively emotional. Then, as now, I loved the costumes. Even then, though I enjoyed the movie, I felt inklings of things I noticed this evening. I could talk, for instance, about the probably well-meaning but not very subtle way in which the film attempts to engage with issues of class or gender. The way that the rollicking party below decks lets us know that people with less money are more authentic, or at least more fun. The way that Rose's mother declares that women's choices are never easy just as she pulls Rose's corset strings tight. Yet something else caught my attention tonight, something I'd missed completely before. Seeing it after all these years, I still remembered the main Rose and Jack plot quite clearly, but the frame narrative hadn't stuck with me as well. Yet tonight I was fascinated by that frame.

The film opens with images of the submerged ship. Mundane objects are strewn about the ocean floor, the only testament to the lived experience of that drowned and broken metal hull. Eyeglasses, a baby-doll, a pair of boots exist in ghostly perpetuity, everyday items made strange by their decontextualization. The ocean, these objects seem to say, is not the natural realm for humans. It swallows us up. Unlike the topography on land, which can be marked by people, the contours of the sea shift continuously, and we can either float to shore or sink to the sandy depths. One must delve deep, quite literally, in order to find any traces of human existence in the ocean. The crew that opens the film, seeking history, fame, and fortune in the wreck, can reconstruct the sinking via computer, but they can't really understand it. They only see material value when they look at the submerged debris. As their inability to interpret the underwater landscape becomes apparent, a drawing of a young woman slowly emerges. They're not sure what to make of that either, except that the woman in the drawing is wearing the costly diamond they want to find.

It is at this point that a sweet elderly woman enters the picture, as if the re-emerged drawing had conjured her from the depths. She joins the crew and tells them all about her memories of the night the Titanic went down. Their fancy equipment can't help them to really understand, but this ancient lady appears just in time to interpret the objects and events for them. All of our images of the original ship and crew and passengers are through this elderly Rose's memory. The primary narrative is therefore invoked by her verbal recollections. For someone who has never spoken of the events before, who never even told her family about Jack, this lady sure can tell her story without a stutter. The men, who've only looked at the wreck for the fortune it could bring them, sit transfixed. They finally see the Titanic.

All of this reminds me of the Middle English poem Saint Erkenwald, which tells the story of an excavation that unearths an ancient tomb. As builders erect a cathedral atop the ruins of a pagan temple, they find a mysterious sarcophagus marked with ancient script. I think it's no accident that this image of palimpsestic architecture unearths such a living relic. While trying to build over history, the workers dig it back up in the form of this strange tomb. All of the most learned men attempt to read the mysterious writing on the tomb and to interpret its meaning. They look at the garments of the body inside the tomb and make conjectures about who he was, perplexed that none of their chronicles mention such a person. None of them can figure it out. As they begin to give into their frustration, they call in Bishop Erkenwald. He prays for guidance, and the long-dead judge buried inside the tomb arises and tells his story from the grave, explaining to them who he was and when he lived. And they finally understand. Erkenwald's understanding and empathy for the dead pagan man get represented physically in the tear he sheds upon learning that the good judge has been in hell all these years, and that tear serves as a kind of baptism that allows the judge's body to dissolve and his soul to rise to heaven. I never understood how the judge can speak English (or some language that the people recognize) when the writing on his tomb is in a language so foreign as to be completely unknown. But that is, I guess, beside the point. The material object from the past is illegible, even the writing from the past is unreadable, so the past needs to be literally revived in order to tell its own story. The resuscitated body of the past can help the people understand in a way that objects and letters never could. Or perhaps the revived body is representative of our attempts to get at that past via the objects and narratives we have. As Christine Chism argues in Alliterative Revivals, "death grants ghosts an interrogative force, imbuing the impossible, unceasing communication between the dead and the living, the past and the present with fearful intimacy" (1). The past is zombie-like in such texts; it rises from the grave and speaks aloud in order that we may hear it.

Though this film is quite different from that Middle English poem, it nonetheless features a past that becomes accessible through a figure emerging and speaking for it. The shot of young Rose's eye morphing into old Rose's eye (again, the film is not trying to be subtle) depicts the direct and physical link between the experience of the sinking ship and the story being narrated today. Though all is mediated via Rose's perspective and memory of long-past events, I suppose we are meant to trust her. If we have any doubts, the fact that she appears at the end with the diamond indicates that she's been conveying the events accurately. She's someone interested in tangible recollections, someone who carries all of her photographs with her when she travels. Yet she admits that she has no photograph of Jack, that there's no record of Jack. He lives on only in her memory. Jack has sunk deep into the sea, not to be brought back to the surface except through Rose's words. For the duration of her tale, the living, breathing, steaming love story can resurface. The captain and Mr Andrews and all the people above and below decks can breathe and speak and live and die as they did so many years ago.

The film could have simply told the story without the frame. It could have begun with Rose and Jack getting on the ship and ended with Jack's death or Rose's survival. It could have even been made from Rose's current perspective, but only in private recollection or more vaguely to us the viewers. Instead, the frame is of people today explicitly seeking something in the wreck and finding it in the person of an old women who once walked the decks of the ship they search. The past emerges bodily and memory is conveyed in color and sound and state-of-the-art special effects. Rose even opens with a description of the smell of fresh paint aboard the ship, a sensory contrast to the rusted and peeling metal we see today. When elderly Rose is finished with her tale, she can finally return to Titanic and to Jack, in dreams or perhaps in death. The narrative has not only brought those around to the ship, but it has returned her to it as well. She rose from the wreckage to tell the story, and then returned to it, along with her heart-shaped necklace.

The past, like the ocean, is never fully accessible to us. We can try to see what lies beneath the waves and we can pull a few things up to the surface, but it is never completely in reach. As a medieval scholar, I understand the frustrations of trying to access the past. And there is no one alive from the 14th century to tell me about it. The image of a body from the past emerging to speak to us is a tantalizing fantasy, as even people's narrations of the past can't actually take us there. Yet it's a fantasy that speaks to our continued longing to plumb those depths, to understand what lies beneath and beyond our own existence as we pass over the same land and through the same waters as people of long ago.

As I sit watching the same film as I did 15 years ago, I see the impossibility of fully understanding or reliving the past, even when that past is my own. On a superficial level, the film is now rendered 3-dimensional, but time has wrought its changes on me as a viewer as well. I notice different things and respond in different ways. My colleagues and I discussed the ways in which films and viewers have changed more broadly. My friend Amanda noted that this movie is situated in its time and place. Post-9-11, its disaster narrative would have meant something very different than it did to us all in 1997. Now we picture the twin towers or think about the socioeconomic realities that allowed some to escape Hurricane Katrina while others could not. I look at pictures of flood and remember the horrifying images from Japan after the recent earthquakes there. The film, already a heavily mediated image of history, is now filtered through all the disasters we've witnessed on the evening news in the past decade and a half. All of these connections make the film and the history it attempts to depict both more and less immediate. And yet it remains as an artifact and we engage with it and with both Roses and with our past selves as we sit in the theater. And we narrate the memories of our previous experiences with the film even as the film gives memory a tangible existence in the person of an elderly lady with a story to tell.

The film opens with images of the submerged ship. Mundane objects are strewn about the ocean floor, the only testament to the lived experience of that drowned and broken metal hull. Eyeglasses, a baby-doll, a pair of boots exist in ghostly perpetuity, everyday items made strange by their decontextualization. The ocean, these objects seem to say, is not the natural realm for humans. It swallows us up. Unlike the topography on land, which can be marked by people, the contours of the sea shift continuously, and we can either float to shore or sink to the sandy depths. One must delve deep, quite literally, in order to find any traces of human existence in the ocean. The crew that opens the film, seeking history, fame, and fortune in the wreck, can reconstruct the sinking via computer, but they can't really understand it. They only see material value when they look at the submerged debris. As their inability to interpret the underwater landscape becomes apparent, a drawing of a young woman slowly emerges. They're not sure what to make of that either, except that the woman in the drawing is wearing the costly diamond they want to find.

It is at this point that a sweet elderly woman enters the picture, as if the re-emerged drawing had conjured her from the depths. She joins the crew and tells them all about her memories of the night the Titanic went down. Their fancy equipment can't help them to really understand, but this ancient lady appears just in time to interpret the objects and events for them. All of our images of the original ship and crew and passengers are through this elderly Rose's memory. The primary narrative is therefore invoked by her verbal recollections. For someone who has never spoken of the events before, who never even told her family about Jack, this lady sure can tell her story without a stutter. The men, who've only looked at the wreck for the fortune it could bring them, sit transfixed. They finally see the Titanic.

All of this reminds me of the Middle English poem Saint Erkenwald, which tells the story of an excavation that unearths an ancient tomb. As builders erect a cathedral atop the ruins of a pagan temple, they find a mysterious sarcophagus marked with ancient script. I think it's no accident that this image of palimpsestic architecture unearths such a living relic. While trying to build over history, the workers dig it back up in the form of this strange tomb. All of the most learned men attempt to read the mysterious writing on the tomb and to interpret its meaning. They look at the garments of the body inside the tomb and make conjectures about who he was, perplexed that none of their chronicles mention such a person. None of them can figure it out. As they begin to give into their frustration, they call in Bishop Erkenwald. He prays for guidance, and the long-dead judge buried inside the tomb arises and tells his story from the grave, explaining to them who he was and when he lived. And they finally understand. Erkenwald's understanding and empathy for the dead pagan man get represented physically in the tear he sheds upon learning that the good judge has been in hell all these years, and that tear serves as a kind of baptism that allows the judge's body to dissolve and his soul to rise to heaven. I never understood how the judge can speak English (or some language that the people recognize) when the writing on his tomb is in a language so foreign as to be completely unknown. But that is, I guess, beside the point. The material object from the past is illegible, even the writing from the past is unreadable, so the past needs to be literally revived in order to tell its own story. The resuscitated body of the past can help the people understand in a way that objects and letters never could. Or perhaps the revived body is representative of our attempts to get at that past via the objects and narratives we have. As Christine Chism argues in Alliterative Revivals, "death grants ghosts an interrogative force, imbuing the impossible, unceasing communication between the dead and the living, the past and the present with fearful intimacy" (1). The past is zombie-like in such texts; it rises from the grave and speaks aloud in order that we may hear it.

Though this film is quite different from that Middle English poem, it nonetheless features a past that becomes accessible through a figure emerging and speaking for it. The shot of young Rose's eye morphing into old Rose's eye (again, the film is not trying to be subtle) depicts the direct and physical link between the experience of the sinking ship and the story being narrated today. Though all is mediated via Rose's perspective and memory of long-past events, I suppose we are meant to trust her. If we have any doubts, the fact that she appears at the end with the diamond indicates that she's been conveying the events accurately. She's someone interested in tangible recollections, someone who carries all of her photographs with her when she travels. Yet she admits that she has no photograph of Jack, that there's no record of Jack. He lives on only in her memory. Jack has sunk deep into the sea, not to be brought back to the surface except through Rose's words. For the duration of her tale, the living, breathing, steaming love story can resurface. The captain and Mr Andrews and all the people above and below decks can breathe and speak and live and die as they did so many years ago.

The film could have simply told the story without the frame. It could have begun with Rose and Jack getting on the ship and ended with Jack's death or Rose's survival. It could have even been made from Rose's current perspective, but only in private recollection or more vaguely to us the viewers. Instead, the frame is of people today explicitly seeking something in the wreck and finding it in the person of an old women who once walked the decks of the ship they search. The past emerges bodily and memory is conveyed in color and sound and state-of-the-art special effects. Rose even opens with a description of the smell of fresh paint aboard the ship, a sensory contrast to the rusted and peeling metal we see today. When elderly Rose is finished with her tale, she can finally return to Titanic and to Jack, in dreams or perhaps in death. The narrative has not only brought those around to the ship, but it has returned her to it as well. She rose from the wreckage to tell the story, and then returned to it, along with her heart-shaped necklace.

The past, like the ocean, is never fully accessible to us. We can try to see what lies beneath the waves and we can pull a few things up to the surface, but it is never completely in reach. As a medieval scholar, I understand the frustrations of trying to access the past. And there is no one alive from the 14th century to tell me about it. The image of a body from the past emerging to speak to us is a tantalizing fantasy, as even people's narrations of the past can't actually take us there. Yet it's a fantasy that speaks to our continued longing to plumb those depths, to understand what lies beneath and beyond our own existence as we pass over the same land and through the same waters as people of long ago.

As I sit watching the same film as I did 15 years ago, I see the impossibility of fully understanding or reliving the past, even when that past is my own. On a superficial level, the film is now rendered 3-dimensional, but time has wrought its changes on me as a viewer as well. I notice different things and respond in different ways. My colleagues and I discussed the ways in which films and viewers have changed more broadly. My friend Amanda noted that this movie is situated in its time and place. Post-9-11, its disaster narrative would have meant something very different than it did to us all in 1997. Now we picture the twin towers or think about the socioeconomic realities that allowed some to escape Hurricane Katrina while others could not. I look at pictures of flood and remember the horrifying images from Japan after the recent earthquakes there. The film, already a heavily mediated image of history, is now filtered through all the disasters we've witnessed on the evening news in the past decade and a half. All of these connections make the film and the history it attempts to depict both more and less immediate. And yet it remains as an artifact and we engage with it and with both Roses and with our past selves as we sit in the theater. And we narrate the memories of our previous experiences with the film even as the film gives memory a tangible existence in the person of an elderly lady with a story to tell.

Labels:

14th century,

9-11,

alliterative revivals,

body,

Chism,

disaster,

Erkenwald,

film,

history,

Hurricane Katrina,

medieval,

memory,

middle english,

narrative,

ocean,

sea,

shipwreck,

St. Erkenwald,

Titanic

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)