Last summer I spent an idyllic weekend at Cape Cod with my close friends, Audrey, Ali, and Hilarie. Audrey's parents graciously hosted us at their lovely home. We enjoyed delicious sea food meals cooked by Audrey's mother, spent quiet moments of reading and yoga in the sunlight-filled backyard, explored the main streets of local towns, and splashed and played in the waters of the beaches. Remembering these moments of peace and excitement and friendship has sustained me through a hectic year. I'd never been to Cape Cod before, and I thoroughly enjoyed exploring the area. I also felt relieved to be near the ocean again. Having spent my whole life within an easy drive from the beach, living in Rochester has been an adjustment for me. Sure, the beaches of Lake Ontario are close by, but a lake is not the ocean, no matter how great it is. (And I feel like the area is taunting me by naming everything around Lake Ontario "Sea Breeze.") During our trip, we went on a whale watching excursion one evening, and were surprised and awed by the whales we saw. Our timing must have been right, because the whales were surrounding our boat, leaping and eating and waving their fins at us.

The naturalist on board counted around 50 whales, and said he'd never seen anything like it. I could not have predicted how delighted I was as these whales emerged from the watery depths. And I was not alone. All around the deck I heard gasps of excitement and joy. Perfect strangers were smiling at each other, exchanging gleeful words, and even high-fiving and hugging. A diverse group of people who had never seen each other before, we were suddenly bonded by our experience with these creatures. We forgot polite distances and social codes of behavior in the face of something so massive. Whales do not come from our world. They are of the water. And yet they're mammals. They can visit us and they can breath in our realm.

As I was watching these humpbacks feed and play, it occurred to me that my reaction (indeed the reactions of everyone on board) was based upon our society's views about (and knowledge of) whales. If we had no understanding of these creatures, if we didn't grow up singing "Baby Beluga" and visiting marine parks, our little excursion would have produced a very different response. Instead of being overjoyed by the experience, we would have been terrified. Glimpses of fin and tail in the water could be easily mistaken for a sea monster. These whales, if they had wanted to, could have overturned our boat with ease. I was reminded of the Anglo-Saxon poem about the whale from the Exeter Book in which the whale is described as a fierce creature that terrifies seafarers.

In an image worthy of a Loony Toons cartoon, the poem describes how sailers sometimes mistake the whale's back for an island. Then the poem takes an eerie turn as the whale waits until the sailers are settled and comfortable on his back only to dive deep and drown them. The whale, we are told, is like the devil, who fools us with earthly pleasures only to draw us down to hell. This poem of insular uncertainty, in which the land we seek may really be part of the water, bears little resemblance to our experience of whales today. But it's not unreasonable to fear these massive water-dwellers if we know nothing of them. The ocean is unimaginably vast; its depths are beyond human exploration. Because we cannot know what lies below the waters, because we are never sure what's lurking beneath us, the ocean is a kind of mysterious wilderness zone. Majestic and beautiful, yes, but a little frightening too. We had faith in the benevolence of the whales we saw that day, and I suppose they had faith in our benevolence as well. Two worlds met for a brief moment, and we were changed because of it.

I attempted to contain this transformational experience with my camera, snapping pictures as quickly as I could and trying to capture the fleeting moments of fin and tail. As hard as I tried, I couldn't fit the larger-than-life adventure through my camera lens. I was reminded of Jeffrey Jerome Cohen's discussion of the body in pieces from his book Of Giants. He explains that, "[w]hen placed inside a human frame of reference, the giant can be known only through synecdoche: a hand that grasps, a lake that has filled his footprint, a shoe or glove that dwarfs the human body by its side. To gaze on the giant as more than a body in pieces requires the adoption of an inhuman, transcendent point of view; yet beside the full form of the giant, the human body dwindles to a featureless outline, like those charts in museums that depict a tiny silhouette of Homo sapiens below a fully realized Tyrannosaurus rex" (xiii).

Cohen was surely inspired in part by Susan Stewart's On Longing, which states that "we know the gigantic only partially" (71). Like the giant, the whale is larger than our eyes can fix upon at any one moment. But even beyond that, only pieces of the whale ever emerge from the water at a time. And the camera can catch only miniaturized glimpses of these pieces. The ocean, too, is only available to us in pieces. We can paint blue onto an atlas or globe, but the ocean in its vastness can only be experienced a little at a time: a stretch of beach, an expanse of waves, a bit of horizontal line in which salty green-blue defines itself against azure sky.

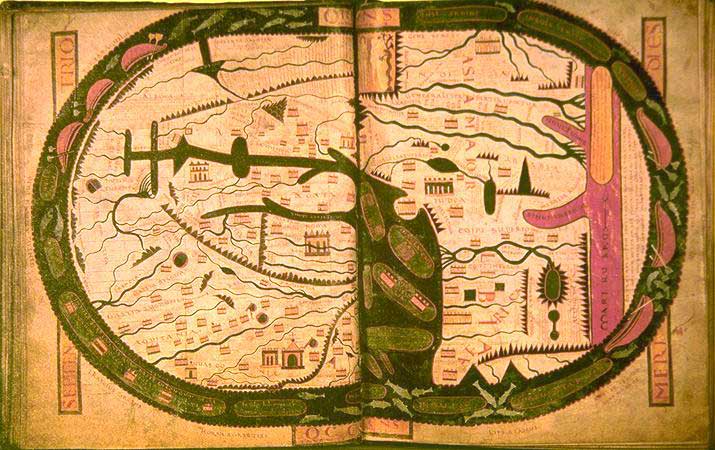

The ocean is an overwhelming presence in the world, surrounding and overlapping the land. To conceptualize it, we must shrink it down. Yet medieval British cartographers took this shrinkage to the extreme, depicting the world with decidedly little water. Medieval mappae mundi were aesthetic and ideological creations. They were images of the world that gave a worldview; they might help you find your place in a spiritual or metaphorical sense, but would be of little service planning a road trip. (See my previous posts on maps here and here.) On these world maps, the further you get from the center, the stranger things become. Yet the ocean in these maps is more marginal than even the monsters, a blank ring around the edge of the world, a circle which bounds and shapes the earth and yet is separate from it. The landed realms in these maps are encyclopedic, covered in the text of biblical and classical and contemporary history. They indicate the connections between topographical features and the historical events that occurred there. The ocean, on the other hand, is a blank ring around that visual-textual landscape.

I would caution that the depiction of the ocean in such maps is not due to ignorance -- mapmakers were certainly aware of the vast watery realm that covers much of the earth -- but instead because the water was not integral to the aims of these maps. The land is the space of history. Humans mark the topography on land and specific locations and events can be recorded. Land is the realm of humankind. The ocean is not our realm. We may float or we may sink, but we are always out of our element when in the water.

Yet the land and sea merge and overlap in unsettling and beautiful ways. The waves push and pull at the shore. Tides go in and out, marking the cycles of day and season even as they shift the boundary between land and water. And under the deepest ocean the sea floor can be found. Islands, too, indicate an uncomfortable land to sea ratio. The ocean surrounds islands as it surrounds mappae mundi, and we can only hope that we're on solid ground instead of on the back of a stealthy creature of the deep.

I absolutely love the quote, "we know the gigantic only partially." I think it could apply to so many elusive, vast, and powerful things, including spiritual experiences and love. I have long fantasized that one version of "heaven" after you die is having sudden access to your entire life as a totality, when you suddenly can see the shape of the whole thing. I picture it being laid out like a map of moments, a series of slices that can be retrieved and put back like little books - perhaps "experienced again" like a memory in a pensieve.

ReplyDeleteI love your posts, Kristi.

Keep writing! Love, Hilarie

Thanks for this beautiful and thoughtful response, Hilarie! I love the idea of a "map of moments," and I think that that was what mappa mundi, in a way, were intended to provide, except for all history instead of one life. Events, like geography, are mapped out for us. What you wrote makes sense to me in terms of how time was conceived. I think that the idea of time being linear or cyclical or even both at once is just an attempt to convey the ways in which it is more than all of these, but our limited perception just won't let us see it. There are medieval images of the stages of man's life in which the timeline of a person is represented as a circle of moments with God in the center, indicating that omniscience allows God access to all of a person's life simultaneously, and those moments only seem to be laid out individually and consecutively because of our lack of omniscience. Mainly I just love the fact that something as linear as progression from birth to old age gets represented as a circle.

DeleteAnother thing I really like about your comment is the idea of the pensieve, the idea that we might "experience again" those things we enjoyed (like this trip, for example). Not only is this an emotionally appealing idea, but I think it speaks to our need for memories to concretely and accurately convey (and connect to) our pasts. The pensieve is memory like no memory we've had, and not just because we can't really re-experience memories, but also because memory is fluid, is shaped by individual perception. Memories in a pensieve are far more concrete than real memory can ever hope to be. But perhaps the memories we'd really like to visit are not concrete or strictly accurate, perhaps they're colored by nostalgia. Maybe many of the meaningful moments in our lives become that way only with knowledge of later events. As we construct narratives of ourselves, we read our pasts back and ascribe meaning to things that might not have felt particularly meaningful at the time. Being able to visit past moments, but with present knowledge and experience, really is evocative. I wonder, if every moment were laid out as you describe, if we would see different patterns or if different meanings would become available to us. Perhaps there's a kind of comfort in the limited life narratives we construct, and surely we can't handle the full kind of awareness you describe, and yet what possibilities it would open up.

Like Kristi, I utterly adore the idea of a map of moments, Hilarie! What an exquisite way to think about the beyond.

DeleteYour comment and Kristi's response reminded me of the concept of the eternal return. I've always been fascinated by the question that Nietzsche (whose name I can NEVER spell correctly on my own, even after all these years) poses in _The Gay Science_:

"What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: 'This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more' ... Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: 'You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine.'"

There have certainly been times in my life, especially in the midst of tragic circumstances, where I would have cursed the messenger, but I can also recall many times where I would have praised the creature instead and been thankful for the knowledge that I'd be able to relive a particular experience again. Joy and sorrow are certainly as cyclic and fluid as memory, I think, and -- as the old adage goes -- we can't truly have one without the other. If our memories shape us and we, in turn, shape our memories, then perhaps the continuous possibility to recontextualize our experiences (whether joyful, sorrowful, or somewhere in between) allows us infinite opportunities to create ourselves anew, even if we are doomed/gifted with equally infinite opportunities to relive the same experiences.

The eternal return is a great connection, Kate! It connects nicely to the idea of a memory/experience map, and also to my discussion of history as both cyclical and teleological. The idea of an eternal return presupposes a past, present, and future and yet also that these can be shifted, overlapped, rearranged. (On a silly side-note, I wonder if the makers of Groundhog's Day had this in mind, in minute form . . .) It also makes me think that perhaps a good life goal would be to live so that the eternal return would be welcome, joyful.

DeleteKristi,

ReplyDeleteThank you for this beautiful post! I'll start pulling my weight on this blog shortly, I promise!

Like you, I have very strong ties to the ocean. There is something about its vastness that inspires both the wonder and sense of connectedness to others that you chronicled in your story and the simultaneously sobering and liberating awareness of how very small we are in the grand scheme of things. I've always taken great comfort from rumble of the waves as a result!

I was struck, in particular, by your discussion of our optical limitations when approaching the gigantic. As Hilarie pointed out, the idea that we can only comprehend the gigantic in a fragmentary way applies to so many aspects of our lives, and I love that we can ultimately choose whether to be excited or discomforted by this fact. In a way, it aligns with what I always tell my students: that no matter how much you master, there will always be an infinite array of things yet to learn. You can either be frustrated by the fact that you'll never be "done," or excited, because there will always be something new to discover!

On a different topic, have you read the book Grayson? I thought of it immediately as I read your post and the comments that followed, and I'd love see how you see it aligning with what you've written about here!

Yes, I think that the ocean is a nice metaphor for our limited perspective, our smallness, and yet I do find it comforting as well. The ocean also connects us in a way. As a literature person, I like the idea that there's always more depth, that even the surface shifts, that we can't really grasp or contain the water and yet we can see the beauty in that. Like you, I love the idea that there's always more to discover.

DeleteI haven't read the novel Grayson, but I will look it up right now. Maybe it will make good summer reading. Thanks for the suggestion and for the lovely and thought-provoking comments, Kate!

Thank you for another beautiful post that ties the medieval to the modern to the eternal and back again. In thinking about rocks this spring, I've been thinking of oceans receded, oceans disappeared, whose only trace now are to be found in the veins and traces of alabaster. When Marbod de Rennes claims that crystals are eternally stilled water he was, of course, on to some thing.

ReplyDeleteQuestion: will you be at Kalamazoo this year?

Thanks for these great comments, Anne! I love the connection between oceans and rocks that you make. The notion that often the only traces of the ocean are on rocks is an evocative one. It's cool how this connects to your own project on alabaster, which I was just reading about on your blog (Medieval Meets World ) The idea of crystals as still water is as especially beautiful one, and reminds me of Mandeville's discussion of diamonds. His description of diamonds is almost more plant-like, and yet he talks about diamonds being watered and grown, so water does seem to play a role in their creation (he also talks about them being male and female, which is fascinating but for another post). Since diamonds and crystals have some similarities (they're often transparent or translucent, for example), it's interesting that each has these connections to water in medieval texts. It seems that there is an attempt to see still and hardened water in clear gemstones (like ice). Since water itself can actually wear away rocks, as you mention, (and isn't sand just rock that's been worn away until it's tiny particles?) it's interesting to see rocks themselves as still water.

DeleteAlso, I will be in Kalamazoo, which is coming up much more quickly than I realized!