I just returned from Kalamazoo, Michigan, where I attended this year's fabulous International Congress on Medieval Studies. Kalamazoo (or, as we medievalists fondly call it, "the zoo") has become an annual pilgrimage for me, a time of year as sure as spring, when a caravan of cars from Rochester heads across the midwest to a magical place where people who study the Middle Ages feel for a few days a year like we might actually make up a significant portion of the population. This was my sixth year going and my fifth year presenting; I've enjoyed it each time, but this year I really felt at home. I'm becoming increasingly relaxed at this conference, which can be a bit overwhelming at first. Made up of scholars from a variety of disciplines, around 3,000 people from around the world attend the congress. I saw some great papers, had some wonderful conversations, and got to catch up with friends old and new. My panel, on "Women and their Environments: Real and Imagined" and sponsored by the Society for Medieval Feminist Scholarship, worked beautifully as a whole. The papers moved us from cityscape to forest to ocean in the course of the panel. (For a fascinating discussion of female bodies and landscape, see

Kate's recent post on

Perceval of Galles.) I came back with pages of notes to fuel my chapter, and am feeling reinvigorated after a long semester/year. Once again, I feel lucky to be in a field with such smart and engaging and generous scholars.

Since I just gave a paper on Chaucer's

Man of Law's Tale at Kalamazoo, and I'll be giving another paper on the same tale for the New Chaucer Society later this summer in Portland, Oregon, I thought I'd write a little about the tale and my experience of it. This post combines random musings with pieces from the paper I just gave, the one I'll give this July, and the chapter in progress. For those of you who need a little refresher, the tale is about Custance, a saintly Roman Princess. She first travels east to marry the Sultan of Syria, who's converted for her love, but her new mother-in-law isn't pleased with the plan and sets her to sea in a rudderless ship. Finally reaching Northumbria, she manages to convert and marry the king there (she has a real talent for looking pretty enough to convert any world leader she encounters). But she once again lands herself an evil mother-in-law. This mother-in-law also sends our heroine on a rudderless ship, but this time she makes it back to Rome. Her royal husband also travels to Rome on pilgrimage, and a happy reunion can occur. This brief summary leaves our many important details, but it will do for now. The tale is part of a larger tradition of Constance narratives which feature the same basic story line, though with important distinctions.

The

Man of Law's Tale is the most famous Middle English iteration of the rudderless ship tales, and also the most famous of the tales in the so-called Constance-Cycle, so I knew that I would have to tackle it in my dissertation. I found this task daunting for multiple reasons. First, it's Chaucer. There's just so much criticism to contend with. At least it's not the Wife of Bath or the Pardoner but it's still breathtaking to consider how many people have read and written on this story and on

The Canterbury Tales more generally. Second, I really didn't know what to do with this tale. I had already figured out my arguments about Gower's version, which features a much more assertive Constance. The Man of Law seems intent on downplaying Custance's free will and in giving her as little agency as possible. I just didn't know what I was going to say beyond contrasting this Constance with other, spunkier Constances, and that didn't seem particularly interesting or original. So I put off this chapter as long as I could.

Last year I included the

Man of Law's Tale in my course on Medieval travel, and teaching the tale helped me to see it in a new way. Re-reading a text in order to teach it and discussing it with students who've never before encountered it always helps me to see it anew. I was also really fascinated by the reactions my students had to Custance. I've taught the

Wife of Bath's Tale several times now, and I've come to expect strong responses from students to the Wife. I really didn't expect Custance to elicit those kinds of emotions. But the students did respond, to both the story and to its heroine. There were students who, like me, were annoyed by Custance's passivity. But others found in her a role model, a person strong and confident in herself and her beliefs. It was quite a diverse group, especially the first semester I taught it, with people from a variety of countries and religious backgrounds, and there were about the same number of males and females in the class. Two of the students who identified most strongly with Custance, who found in her a role model for themselves, were male. They were both people of faith, but people from very different religious backgrounds, and they saw in her characteristics that they felt all people should strive to possess. These passionate responses made me take a step back and reassess the character. This is not to say that I don't think Custance's faith is gendered or that it doesn't take on specific meanings in the context of the period or of

The Canterbury Tales, but rather that there might simply be aspects of it that I hadn't considered. I began to think about other features of the tale that I might have missed.

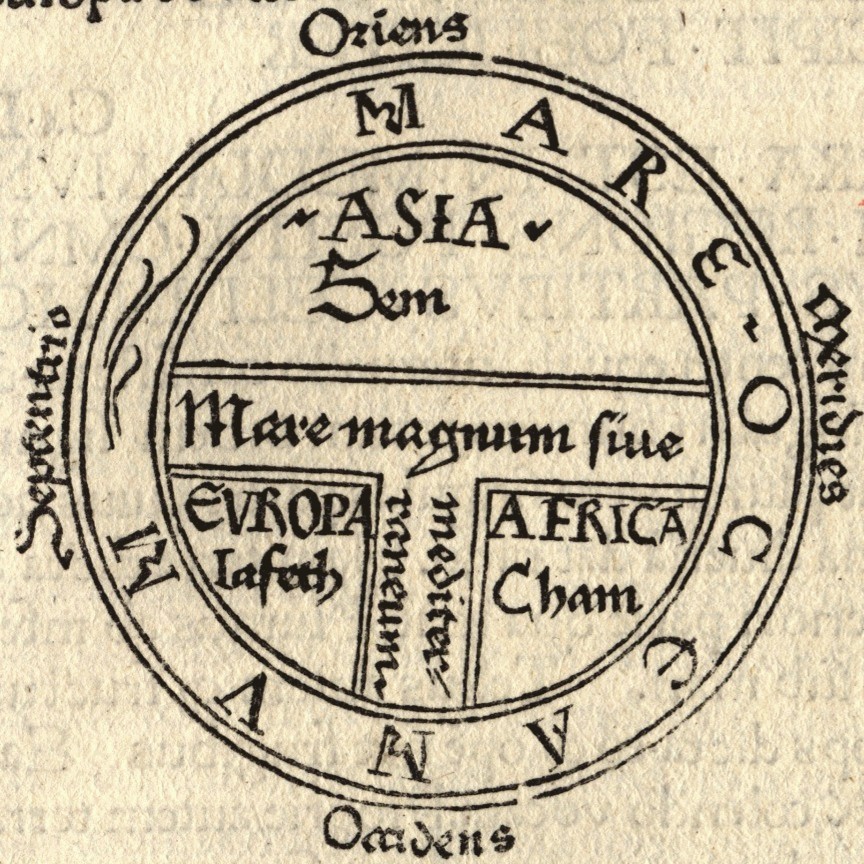

During this time, I was developing my overarching argument about the ocean in the

mappae mundi (which you can find more on

here and

here), and increasingly noticing how blank and marginal a space it was in these maps, on the fringes of the text-covered landscape. The land is history, both linear and cyclical, while the ocean shapes history and yet remains outside of it. Given these features of the

mappae mundi, I began to notice something about the oceanic moments of the tale. On Custance's rudderless voyages, the Man of Law makes sense of her survival by comparing her to a litany of Biblical figures. If we wonder how she survives, we might ask who saved Daniel in the lion's den, who saved Jonah from the Whale, and a quite extensive number of similar questions. These long digressions of comparisons to Biblical figures, which I had found frustrating before, suddenly took a new meaning for me. I had really only thought about how they downplayed Custance's free-will, and that's certainly true, but perhaps something else is going on as well in these lengthy interruptions. If the ocean is extrahistorical, then what do we make of all of these comparisons to figures and events who belong in the historical, landed realm?

There is some precedence for seeing Custance's story in terms of medieval cartography. V.A. Kolve notes in

Chaucer and the Imagery of Narrative that "the tale creates a residual image that is geographical: a map of Europe with a boat moving upon its waters" (319). Kathy Lavezzo expands this notion in

Angels on the Edge of the World by arguing that "since Custance's journey begins in Syria, the cartographic territory evoked in the tale in fact extends beyond Europe and [. . .] suggests a map of the world" (95). David Raybin (who was actually at my talk and who gave me extensive and helpful feedback) joins Custance's geographical marginality with history and time in "Custance and History: Woman as Outsider in Chaucer's

Man of Law's Tale." He notes that "[s]he is exiled from the temporal world and thus unconstrained by time, bound to her faith and thus spiritually free, existing in an emblematic position largely outside of human contact, outside history" (69). All of these scholars have made fascinating and apt arguments about Custance, about her placement in the world. I would like to combine the cartographic discussions of Kolve and Lavezzo with Raybin's ideas about Custance's temporal marginalization, and put all of these in terms of the oceanic spaces of the tale. I want to consider the ocean in the tale as a complex kind of narrative space.

Custance's initial voyage to Syria is barely described. She has a clear destination and a clear purpose (and, presumably, a mode of steering). This trip seems to occur squarely in the historical realm. Her subsequent sea voyages are quite different. Pushed into a rudderless ship and sent into the sea, Custance enters a different kind of narrative space, once in which her prayers and her constant faith can serve her well. Unlike the voyage to Syria, her latter travels occur in a zone outside of history and narrative control. The "salte see" becomes a realm dominated by fate. Only Custance, constant as she is, could survive such a voyage in the oceanic realm. She sails without destination or control. The narrator explains that her boat goes "Som-tyme West, som-tyme North and South,/ And som-tyme Est, ful many a wery day" (948-949). Each cardinal direction is given its turn, making this journey one that can be mapped and yet also one that cannot. We know that the ship takes each direction, so directions are available, which seems more like the real ocean than the circle around the

mappae mundi. Yet the fact that the boat takes each direction at will and we never know quite where we are leads us to that metaphorical realm. Nor is time less fluid than location. The ship is carried back and forth across the ocean for "Yeres and dayes," a time that seems specific, with the addition of days, and yet is nonetheless vague (463). How many years? How many days? Time, it seems, is hard to quantify on the waves. The precise way in which the events of the tale up to this point have been recounted gives way to a rise and fall of detail in keeping with the movement of the ocean itself. On our heroine's second "stereless" voyage the time is somewhat clearer -- "Fyve yeer and more" (902). We do get a number of years this time, but the "and more" undoes that specificity. Temporalities and teleologies and cycles are all lost amid the waves.

Yet the Man of Law must somehow narrate this "stereless" section of the tale, and he does so by connecting Custance's situation with biblical figures who also survived certain death in the form of natural adversaries. As soon as Custance is afloat at sea, outside of the historical realm and in that blank space off the charted map, the Man of Law begins to make connections between our heroine and the sort of men and women who routinely show up on the landed areas of the map. The Man of Law can only make sense of Custance's foray outside of the historical realm by relating it back to that realm in every way possible. He tells us about how Daniel survived the lion's den, Jonah made it out of the whale's belly, the Hebrews passed through the water thanks to the parting of the waves. The comparisons go on for some time, but I would like to consider the fact that these last two, Jonah and the Red Sea, are watery comparisons. While the ocean comparisons may seem fitting to the ocean realm, I would argue that they remain a part of the historical narrative, the kind that was not written into the oceans of the

mappae mundi. By mentioning them here, the Man of Law is simultaneously pulling Custance back into the historical realm and marking the ocean as a space that has contained human history. It is a means of inscribing these events onto the ocean, as so many events were written onto the landscape in medieval world maps.

I argue that these comparisons, extensive and disruptive as they are, serve to reconnect the ocean and land, to renegotiate the tensions involved in a narrative outside of the historical realm. Custance, passive as she is, makes a central and historical narrative out of a blank marginal space. Her story doubles back on itself in the course of her tale; everything occurs more than once, indicating a kind of cyclical history, and yet, as Suzanne Conklin Akbari has noted in a recent talk at the University of Rochester, the story denies us either a complete cycle or a complete teleology. It is both cyclical and linear and it is neither. It moves in and out of historical time, and never allows Custance, or the reader, a clear footing in either realm. The heroine's movements around the earth in her rudderless ship unsettle boundaries and binaries of time and space even as they assert them. The ocean is both vital and distant, encompassing land masses but existing beyond and outside of those realms. It serves as a threshold to other lands, and yet is a distinct conduit, unlike a road, which is built into the land itself. As a conduit not created by humans, it is far more threatening and unpredictable. Because of its placement on

mappae mundi, it also exists outside of history, functioning as an extrahistorical realm. Custance’s oceanic travels thus represent a new kind of storytelling that is – like the ocean – a threshold, a liminal space between kinds of narratives. The realms of land and sea, and the types of narratives embodied by each, are not as separate as they might appear on the map; likewise, modes of narrative production intersect in dynamic ways throughout the tale and allow for the passive Custance to reshape the religio-cultural contours of her world.