In keeping with my tradition of writing a holiday blog (started last year with

Gawain and the Green Knight), I would like to write this year on another of my favorite medieval Christmas stories,

The Second Shepherds' Pageant.

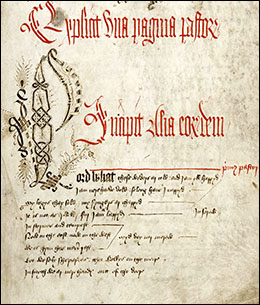

The Second Shepherds' Pageant, also called

The Second Shepherds' Play, has been burdened with its confusing title simply because it's the second play on shepherds in the Towneley manuscript (though the two weren't necessarily meant to be performed as a pair). Though the play is anonymous, the author has become known as the Wakefield Master. The play inserts common shepherds into the nativity story, and it combines social commentary and humor with piety. Simultaneously medieval England and biblical Bethlehem, the play is a beautiful example of the ways in which biblical stories were alive for medieval people through medieval dramatic practices.

The play opens with a lone shepherd's complaint. The weather is cold, and conditions are intolerable for poor men, who are beaten down by hard living and made submissive to the gentry. Both the weather and the social structures described sound an awful lot like late medieval England. As other shepherds arrive on the scene, squabbling (good-natured and otherwise) ensues. When Mak, a man of unsavory reputation, makes an appearance, the shepherds greet him with suspicion. Their suspicion soon proves well-founded, as Mak slips away while the shepherds nap and steals a prize sheep. He takes it to his wife, Gill, and the two concoct a plan. If the shepherds come looking for their missing sheep, they will put the lamb in their cradle and Gill will pretend to be in childbirth. Mak and Gill are known for having children constantly (sometimes twice a year, Mak complains earlier in the play), so her sudden condition shouldn't take any one by surprise. The trick works well at first. The shepherds do show up quickly (and angrily) to seek their lost lamb, but Mak begs them to pity his wife in her childbed while Gill makes terrible moans. The shepherds finally leave, and Mak and Gill breathe a sigh of relief. But then one shepherd realizes that he gave the new baby no gift, and the others respond in kind. Their generosity proves troublesome for our thieving couple, when the shepherds return and pull the swaddling clothes aside to present the child with birthday presents. They cry out that the child is a monster, and then recognize that monster as their own missing lamb. It's no accident that they only discover their lamb once they turn from anger against Mak and Gill to generosity toward the "child." At this point the play, so farcical in tone, could turn deadly. The shepherds have a right to execute Mak for what he's done. After some deliberation, they turn merciful and decide to toss him up in a blanket instead, a humorous solution to the problem. Tired out, they lie in their field to sleep. As if in response to their mercy, a star appears and an angel tells the shepherds of the birth of a savior. They go to seek the Christ child in his manger, and this time they do remember gifts. They give cherries, a bird, and a ball (meant to symbolize life in a time of death, the holy spirit, and a royal orb, respectively). This story, an alternate to the Magi, shows us not wise men, but everymen. They are common shepherds, people the audience might know, granted entrance into the joyous and miraculous scene of the nativity itself.

The setting of the play is particularly resonant, since it is always both Yorkshire and the Holy Land. The characters talk of walking on the moors, and mention many English locations throughout the play. When Mak first arrives, he pretends to speak with a southern English accent, and the others tease him until he resumes his customary Yorkshire speech. People and place all seem firmly located around Wakefield itself. Yet when the star appears, the shepherds need not travel far to find Bethlehem. And, as David Bevington notes in his

Medieval Drama, there would have been two platforms for the play. Mak and Gill's house would have been parallel to the manger on the set, with the shepherds' field in between, connecting the two and presumably holding the audience as well. Bevington explains how the staging gives "a visible form to the parallelism of the farcical and serious action. Although the Wakefield Master never calls explicit attention to the resemblance between the two births, the stage itself would help make the point" (384). The playing space would have visually enacted the themes of the play, yoking together sacred and profane, past and present, there and here. For many people in medieval England, the Bible itself was inaccessible. Books were expensive and the Bible was in Latin. Medieval Drama was thus an important way in which people of the period engaged with scriptural material in a highly interactive way. They wrote and acted in these plays. They stood in their city centers among biblical set-pieces and cheered and laughed and booed and cried. Perhaps they threw things at devils and perhaps they sang along with songs they knew. Puritans were horrified by such spectacles, wanting people to have access to scripture itself instead. But the plays give us insight into the way people of late medieval England saw these as living stories, as stories that were real parts of their own lives and with which they could engage actively. Real emotions, including humor, could be part of sacred drama. Biblical time and place collapsed with contemporary English spaces. The

Second Shepherds' Play takes the collapse of time and place to an extreme as the play inserts Yorkshire shepherds into the nativity. In fact, the majority of the play follows these shepherds, who could be anyone from anywhere and anytime, and yet are also clearly from Yorkshire. It's not until the star appears near the end of the play that we get any overt hint that this is a Christmas story. The play seems to suggest that even mundane moments can be part of a miraculous larger narrative, that we are all part of this narrative together and that it thus continues to have real existence in the world.

I had the good fortune to see the play performed at the

Folger Institute several years ago when my good friend and colleague Dan Stokes and I participated in an Early English Drama workshop there, and the performance was engaging, beautiful, hilarious, and moving. I laughed; I cried. I know that sounds cliché, but I really did laugh and cry over the course of the production. And I wasn't the only one. The most amazing part was the mixed audience. Scholar of medieval drama sat next to families with small children, and all were captivated. Dan and I were having a pint at the pub after the performance, and we saw the actor who played Mak there. When we told him how much we'd enjoyed it, he was thrilled and offered to buy us a round. Apparently, the actors had been terribly nervous that night, since they knew that the academics were coming to the show. We reassured him that they had managed to make the play both wonderfully accessible and scholarly fascinating. In fact, I found it fitting that this play had remained so engaging to so wide an audience. The way in which the play infuses the familiar and yet incredible story of the nativity with everyday people and their hijinks is striking even to modern audiences. The way that these quarreling, complaining, scheming characters can be so moved by the baby in the manger lends the final scene a real sense of awe.

As funny as the play is, the ending is surprisingly poignant. These characters we have come to know seem a bit awkward in the holy scene, but they are so genuinely enamored with the baby that it's hard not to feel a shared sense of joy in the moment. Their gifts to the child may be simple, but they are heartfelt. And the manger is a humble space not unfamiliar to our common shepherds. A play that could have ended in death (either of the sheep or of Mak), ends instead in miraculous birth. And while the symbolism of the lamb in not lost, nor is the audience unaware of the larger story which includes the Passion, we are allowed for a moment, like the shepherds, to just enjoy the scene. Affective piety was popular in the later Middle Ages, and holy people imagined themselves at the foot of the cross and felt the pain and sorrow of that moment.

The Second Shepherds' Play gives us a chance for a different kind of affective engagement, one in which we place ourselves instead in the manger and feel the shared joy. After I saw the play performed, the group of us remarked at how moving it was to all of us, despite our different belief systems. The message is one of mercy and joy and hope, a sense that any one of us could play a part at any moment in something greater than ourselves. This year has been difficult for many, and these last few weeks filled with unimaginable heartache (see Kate's recent beautiful post on the

Coventry Carol). I only hope that we can respond to tragedy with compassion. Like the red cherries picked in the frozen white winter, like the baby born when nights are longest and days are coldest, even the bleakest moments are available to hope and beauty. And the beauty of basic human compassion is that we all have the power to bring it into the world. Perhaps this is the perfect time to think about how the simplest things can be miraculous. Even moments that are common or silly or petty or sad can be made precious if we remember to treat each other with kindness. With that in mind, I wish you all a season filled with love.