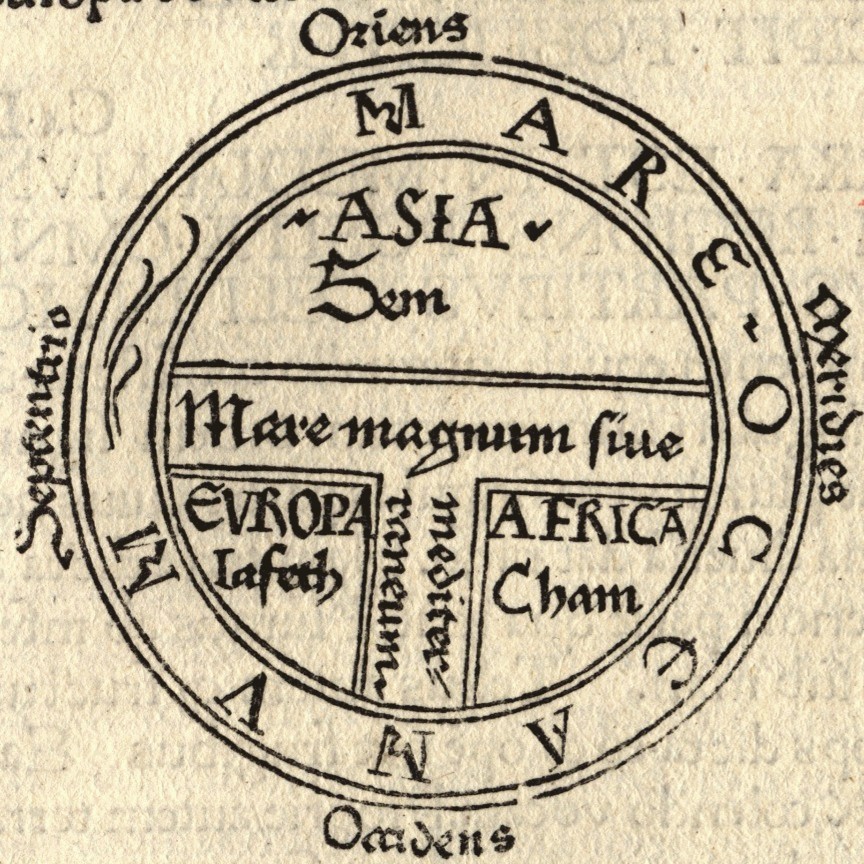

To continue my earlier post on maps, I thought I would go into some of the details of the mappa mundi. As many of you may know, the basic form for these maps is called the T-O map, since the main structure is a "T" inside an "O." The T and O are formed by water, so that the water bounds and shapes and encloses the land, even though the land takes up most of the space and is the focus of the map. The T is the Rivers -- the Mediterranean, the Nile, and the Tanais (i.e. the Don). The O is the ocean, a nameless circle that surrounds the land. The T also separates the continents, with Asia on top, Europe on the bottom left, and Africa on the bottom right. You can see in the above map that each continent is associated with one of Noah's sons: Asia with Sem (Shem), Europe with Iafeth (Japheth), and Africa with Cham (Ham). Jerusalem is at the middle of these maps, where the rivers and continents meet. This location means that Jerusalem was literally the center of the world, the most central and important location available. Move further from that center and things get . . . stranger. On the edges of the map are the so-called monstrous races. Human-like creatures with single feet, or with no heads, or with dog heads, populate the margins of the earth, far from Jerusalem and yet still part of the landed realms. An early (and still very informative) work about the monstrous races is John Bloch Friedman's The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought. There's also much interesting work being done on the placement of Great Britain on these maps, and more still to do. Both Asa Simon Mittman and Kathy Lavezzo have discussed the meaning for England, and English map-makers, that Great Britain is also on the edge of the world in these maps, and I suggest their work to those interested in the topic.

When I teach these maps, I try to get the students to discover the ways in which modern maps are constructed as well. We look at modern maps and discuss the things that aren't directly representative of the geography the maps depict. We talk about those things we've naturalized to the point of thinking they're just true. Since the aspect that surprises the students the most about medieval maps is that Asia is on top, I like to show them an Australian map which flips our normal sense of north as up. I ask why north is on top other than the fact that we've always seen it that way. Who decided? Maybe the fact that compasses point north (for now) had something to do with it, but it still has become the normal depiction to the point that most people think it's somehow natural. The "upside-down map" looks strange, the shapes of the continents unfamiliar, and this defamiliarization is useful for a number of reasons. One is that it helps us to see the geography anew, to attend to the details, since we rarely look as closely at the familiar (like the art assignment where students draw the human face upside-down). Another is that it allows us to think through the implications of the choices the mapmaker has made. What does it mean for north to be on top? What does it mean for Europe to be in the center? What does it mean to choose a projection which contracts and expands different parts of the world? I'm reminded of an episode of West Wing in which "The Organization of Cartographers for Social Equality" take their case to C.J. Cregg. At first, she laughs at the idea of maps having anything to do with social justice. But they show her how different projections alter the image of the earth, and her jaw drops as she realizes that they have a point.

Maybe I'll show that clip next time I teach this material.In any case, looking at different projections and different versions of world maps is a useful exercise, and we're all more ready to discuss the mappae mundi when we return to them. Yes, they're strange, but they're not stupid. And there's nothing inherently wrong with putting east on top. The verb orient comes from the fact that maps were originally oriented to the East (the Orient).

There is much to say about all of this, but I want to focus here on what is barely apparent on the maps: the ocean. Though the ocean forms the "O" and bounds the circle of the land, it nonetheless takes up very little space on the maps. We moderns, used to maps that depict the ocean as more than 70% of the earth's surface, may be surprised to see just how little ocean there is on these medieval world maps. I argue that this is not because medieval mapmakers misunderstood the ocean's vastness, but rather because their maps were ideological, encyclopedic, and aesthetic creations, and the ocean's place around the edges suited these purposes. It left the map symmetrical, but also left the land, and therefore those things that had happened on land, as the primary focus. The land in these maps is covered in classical and biblical and historical details associated with the various spaces on the earth. Humans are at the center of this narrative, and the land is humanity's realm.

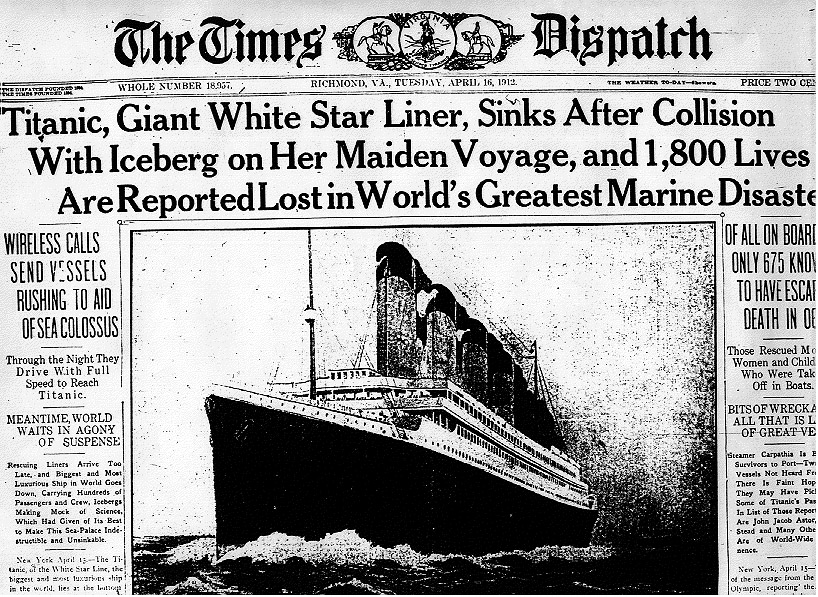

There were other kinds of maps for navigating the ocean, and portolan charts helped seafarers from the 13th century on. The fact that mappae mundi and navigational maps were being produced simultaneously indicates that neither was meant to supersede or replace the other; they were simply for different purposes. The mappae mundi did precisely what they were meant to do -- they gave order to geographical and historical and spiritual information. And the land, and all of the things that had happened there in human history, was the focal point. The ocean is an unmarked space surrounding and outside of the land, more marginal indeed than the monsters that populate the edges of the world. The story is on the land, not the ocean, and thus the ocean depicts nothing; it is simply there to gird the earth. Unlike land, the ocean's topography cannot be marked or altered. It's both vast and unaffected (unaffectable) by humans. The contours of the ocean are ever-changing waves. How can you point to a historical location on the shifting contours of the water? How do you make your presence known to later people when you're floating on the sea? Humans may venture out onto the waters of the world in little wooden vessels, but these vessels will either be brought back to harbor or they will sink into the deep. (See my last post on Titanic for more about that.) No man-made contraptions can stay on the ocean's surface, none can leave a trace of human presence except in the depths of the ocean floor, subsumed by the ocean itself.

So the ocean is a blank space on these mappae mundi. It does not partake in the narrative domain of the land, nor does it participate in the historical or ideological aims of the land. It is a realm apart.

Friday, April 27, 2012

Saturday, April 14, 2012

Dredging up the Past: Titanic and the Body of Memory

I just saw Titanic in 3D. I hadn't thought much about going to see it, and had even laughed at this rerelease as an easy money-making endeavor. Yet when some friends asked me to join, I went. I hadn't seen the film since it was in theaters the last time, before it won too many awards and became a parody of itself (i.e. "I'm king of the wooorld!"). I saw it on my first real date, cliche as that may be, and watched it with a mixed response. For the teenaged me, it was sad and awkward and romantic and manipulatively emotional. Then, as now, I loved the costumes. Even then, though I enjoyed the movie, I felt inklings of things I noticed this evening. I could talk, for instance, about the probably well-meaning but not very subtle way in which the film attempts to engage with issues of class or gender. The way that the rollicking party below decks lets us know that people with less money are more authentic, or at least more fun. The way that Rose's mother declares that women's choices are never easy just as she pulls Rose's corset strings tight. Yet something else caught my attention tonight, something I'd missed completely before. Seeing it after all these years, I still remembered the main Rose and Jack plot quite clearly, but the frame narrative hadn't stuck with me as well. Yet tonight I was fascinated by that frame.

The film opens with images of the submerged ship. Mundane objects are strewn about the ocean floor, the only testament to the lived experience of that drowned and broken metal hull. Eyeglasses, a baby-doll, a pair of boots exist in ghostly perpetuity, everyday items made strange by their decontextualization. The ocean, these objects seem to say, is not the natural realm for humans. It swallows us up. Unlike the topography on land, which can be marked by people, the contours of the sea shift continuously, and we can either float to shore or sink to the sandy depths. One must delve deep, quite literally, in order to find any traces of human existence in the ocean. The crew that opens the film, seeking history, fame, and fortune in the wreck, can reconstruct the sinking via computer, but they can't really understand it. They only see material value when they look at the submerged debris. As their inability to interpret the underwater landscape becomes apparent, a drawing of a young woman slowly emerges. They're not sure what to make of that either, except that the woman in the drawing is wearing the costly diamond they want to find.

It is at this point that a sweet elderly woman enters the picture, as if the re-emerged drawing had conjured her from the depths. She joins the crew and tells them all about her memories of the night the Titanic went down. Their fancy equipment can't help them to really understand, but this ancient lady appears just in time to interpret the objects and events for them. All of our images of the original ship and crew and passengers are through this elderly Rose's memory. The primary narrative is therefore invoked by her verbal recollections. For someone who has never spoken of the events before, who never even told her family about Jack, this lady sure can tell her story without a stutter. The men, who've only looked at the wreck for the fortune it could bring them, sit transfixed. They finally see the Titanic.

All of this reminds me of the Middle English poem Saint Erkenwald, which tells the story of an excavation that unearths an ancient tomb. As builders erect a cathedral atop the ruins of a pagan temple, they find a mysterious sarcophagus marked with ancient script. I think it's no accident that this image of palimpsestic architecture unearths such a living relic. While trying to build over history, the workers dig it back up in the form of this strange tomb. All of the most learned men attempt to read the mysterious writing on the tomb and to interpret its meaning. They look at the garments of the body inside the tomb and make conjectures about who he was, perplexed that none of their chronicles mention such a person. None of them can figure it out. As they begin to give into their frustration, they call in Bishop Erkenwald. He prays for guidance, and the long-dead judge buried inside the tomb arises and tells his story from the grave, explaining to them who he was and when he lived. And they finally understand. Erkenwald's understanding and empathy for the dead pagan man get represented physically in the tear he sheds upon learning that the good judge has been in hell all these years, and that tear serves as a kind of baptism that allows the judge's body to dissolve and his soul to rise to heaven. I never understood how the judge can speak English (or some language that the people recognize) when the writing on his tomb is in a language so foreign as to be completely unknown. But that is, I guess, beside the point. The material object from the past is illegible, even the writing from the past is unreadable, so the past needs to be literally revived in order to tell its own story. The resuscitated body of the past can help the people understand in a way that objects and letters never could. Or perhaps the revived body is representative of our attempts to get at that past via the objects and narratives we have. As Christine Chism argues in Alliterative Revivals, "death grants ghosts an interrogative force, imbuing the impossible, unceasing communication between the dead and the living, the past and the present with fearful intimacy" (1). The past is zombie-like in such texts; it rises from the grave and speaks aloud in order that we may hear it.

Though this film is quite different from that Middle English poem, it nonetheless features a past that becomes accessible through a figure emerging and speaking for it. The shot of young Rose's eye morphing into old Rose's eye (again, the film is not trying to be subtle) depicts the direct and physical link between the experience of the sinking ship and the story being narrated today. Though all is mediated via Rose's perspective and memory of long-past events, I suppose we are meant to trust her. If we have any doubts, the fact that she appears at the end with the diamond indicates that she's been conveying the events accurately. She's someone interested in tangible recollections, someone who carries all of her photographs with her when she travels. Yet she admits that she has no photograph of Jack, that there's no record of Jack. He lives on only in her memory. Jack has sunk deep into the sea, not to be brought back to the surface except through Rose's words. For the duration of her tale, the living, breathing, steaming love story can resurface. The captain and Mr Andrews and all the people above and below decks can breathe and speak and live and die as they did so many years ago.

The film could have simply told the story without the frame. It could have begun with Rose and Jack getting on the ship and ended with Jack's death or Rose's survival. It could have even been made from Rose's current perspective, but only in private recollection or more vaguely to us the viewers. Instead, the frame is of people today explicitly seeking something in the wreck and finding it in the person of an old women who once walked the decks of the ship they search. The past emerges bodily and memory is conveyed in color and sound and state-of-the-art special effects. Rose even opens with a description of the smell of fresh paint aboard the ship, a sensory contrast to the rusted and peeling metal we see today. When elderly Rose is finished with her tale, she can finally return to Titanic and to Jack, in dreams or perhaps in death. The narrative has not only brought those around to the ship, but it has returned her to it as well. She rose from the wreckage to tell the story, and then returned to it, along with her heart-shaped necklace.

The past, like the ocean, is never fully accessible to us. We can try to see what lies beneath the waves and we can pull a few things up to the surface, but it is never completely in reach. As a medieval scholar, I understand the frustrations of trying to access the past. And there is no one alive from the 14th century to tell me about it. The image of a body from the past emerging to speak to us is a tantalizing fantasy, as even people's narrations of the past can't actually take us there. Yet it's a fantasy that speaks to our continued longing to plumb those depths, to understand what lies beneath and beyond our own existence as we pass over the same land and through the same waters as people of long ago.

As I sit watching the same film as I did 15 years ago, I see the impossibility of fully understanding or reliving the past, even when that past is my own. On a superficial level, the film is now rendered 3-dimensional, but time has wrought its changes on me as a viewer as well. I notice different things and respond in different ways. My colleagues and I discussed the ways in which films and viewers have changed more broadly. My friend Amanda noted that this movie is situated in its time and place. Post-9-11, its disaster narrative would have meant something very different than it did to us all in 1997. Now we picture the twin towers or think about the socioeconomic realities that allowed some to escape Hurricane Katrina while others could not. I look at pictures of flood and remember the horrifying images from Japan after the recent earthquakes there. The film, already a heavily mediated image of history, is now filtered through all the disasters we've witnessed on the evening news in the past decade and a half. All of these connections make the film and the history it attempts to depict both more and less immediate. And yet it remains as an artifact and we engage with it and with both Roses and with our past selves as we sit in the theater. And we narrate the memories of our previous experiences with the film even as the film gives memory a tangible existence in the person of an elderly lady with a story to tell.

The film opens with images of the submerged ship. Mundane objects are strewn about the ocean floor, the only testament to the lived experience of that drowned and broken metal hull. Eyeglasses, a baby-doll, a pair of boots exist in ghostly perpetuity, everyday items made strange by their decontextualization. The ocean, these objects seem to say, is not the natural realm for humans. It swallows us up. Unlike the topography on land, which can be marked by people, the contours of the sea shift continuously, and we can either float to shore or sink to the sandy depths. One must delve deep, quite literally, in order to find any traces of human existence in the ocean. The crew that opens the film, seeking history, fame, and fortune in the wreck, can reconstruct the sinking via computer, but they can't really understand it. They only see material value when they look at the submerged debris. As their inability to interpret the underwater landscape becomes apparent, a drawing of a young woman slowly emerges. They're not sure what to make of that either, except that the woman in the drawing is wearing the costly diamond they want to find.

It is at this point that a sweet elderly woman enters the picture, as if the re-emerged drawing had conjured her from the depths. She joins the crew and tells them all about her memories of the night the Titanic went down. Their fancy equipment can't help them to really understand, but this ancient lady appears just in time to interpret the objects and events for them. All of our images of the original ship and crew and passengers are through this elderly Rose's memory. The primary narrative is therefore invoked by her verbal recollections. For someone who has never spoken of the events before, who never even told her family about Jack, this lady sure can tell her story without a stutter. The men, who've only looked at the wreck for the fortune it could bring them, sit transfixed. They finally see the Titanic.

All of this reminds me of the Middle English poem Saint Erkenwald, which tells the story of an excavation that unearths an ancient tomb. As builders erect a cathedral atop the ruins of a pagan temple, they find a mysterious sarcophagus marked with ancient script. I think it's no accident that this image of palimpsestic architecture unearths such a living relic. While trying to build over history, the workers dig it back up in the form of this strange tomb. All of the most learned men attempt to read the mysterious writing on the tomb and to interpret its meaning. They look at the garments of the body inside the tomb and make conjectures about who he was, perplexed that none of their chronicles mention such a person. None of them can figure it out. As they begin to give into their frustration, they call in Bishop Erkenwald. He prays for guidance, and the long-dead judge buried inside the tomb arises and tells his story from the grave, explaining to them who he was and when he lived. And they finally understand. Erkenwald's understanding and empathy for the dead pagan man get represented physically in the tear he sheds upon learning that the good judge has been in hell all these years, and that tear serves as a kind of baptism that allows the judge's body to dissolve and his soul to rise to heaven. I never understood how the judge can speak English (or some language that the people recognize) when the writing on his tomb is in a language so foreign as to be completely unknown. But that is, I guess, beside the point. The material object from the past is illegible, even the writing from the past is unreadable, so the past needs to be literally revived in order to tell its own story. The resuscitated body of the past can help the people understand in a way that objects and letters never could. Or perhaps the revived body is representative of our attempts to get at that past via the objects and narratives we have. As Christine Chism argues in Alliterative Revivals, "death grants ghosts an interrogative force, imbuing the impossible, unceasing communication between the dead and the living, the past and the present with fearful intimacy" (1). The past is zombie-like in such texts; it rises from the grave and speaks aloud in order that we may hear it.

Though this film is quite different from that Middle English poem, it nonetheless features a past that becomes accessible through a figure emerging and speaking for it. The shot of young Rose's eye morphing into old Rose's eye (again, the film is not trying to be subtle) depicts the direct and physical link between the experience of the sinking ship and the story being narrated today. Though all is mediated via Rose's perspective and memory of long-past events, I suppose we are meant to trust her. If we have any doubts, the fact that she appears at the end with the diamond indicates that she's been conveying the events accurately. She's someone interested in tangible recollections, someone who carries all of her photographs with her when she travels. Yet she admits that she has no photograph of Jack, that there's no record of Jack. He lives on only in her memory. Jack has sunk deep into the sea, not to be brought back to the surface except through Rose's words. For the duration of her tale, the living, breathing, steaming love story can resurface. The captain and Mr Andrews and all the people above and below decks can breathe and speak and live and die as they did so many years ago.

The film could have simply told the story without the frame. It could have begun with Rose and Jack getting on the ship and ended with Jack's death or Rose's survival. It could have even been made from Rose's current perspective, but only in private recollection or more vaguely to us the viewers. Instead, the frame is of people today explicitly seeking something in the wreck and finding it in the person of an old women who once walked the decks of the ship they search. The past emerges bodily and memory is conveyed in color and sound and state-of-the-art special effects. Rose even opens with a description of the smell of fresh paint aboard the ship, a sensory contrast to the rusted and peeling metal we see today. When elderly Rose is finished with her tale, she can finally return to Titanic and to Jack, in dreams or perhaps in death. The narrative has not only brought those around to the ship, but it has returned her to it as well. She rose from the wreckage to tell the story, and then returned to it, along with her heart-shaped necklace.

The past, like the ocean, is never fully accessible to us. We can try to see what lies beneath the waves and we can pull a few things up to the surface, but it is never completely in reach. As a medieval scholar, I understand the frustrations of trying to access the past. And there is no one alive from the 14th century to tell me about it. The image of a body from the past emerging to speak to us is a tantalizing fantasy, as even people's narrations of the past can't actually take us there. Yet it's a fantasy that speaks to our continued longing to plumb those depths, to understand what lies beneath and beyond our own existence as we pass over the same land and through the same waters as people of long ago.

As I sit watching the same film as I did 15 years ago, I see the impossibility of fully understanding or reliving the past, even when that past is my own. On a superficial level, the film is now rendered 3-dimensional, but time has wrought its changes on me as a viewer as well. I notice different things and respond in different ways. My colleagues and I discussed the ways in which films and viewers have changed more broadly. My friend Amanda noted that this movie is situated in its time and place. Post-9-11, its disaster narrative would have meant something very different than it did to us all in 1997. Now we picture the twin towers or think about the socioeconomic realities that allowed some to escape Hurricane Katrina while others could not. I look at pictures of flood and remember the horrifying images from Japan after the recent earthquakes there. The film, already a heavily mediated image of history, is now filtered through all the disasters we've witnessed on the evening news in the past decade and a half. All of these connections make the film and the history it attempts to depict both more and less immediate. And yet it remains as an artifact and we engage with it and with both Roses and with our past selves as we sit in the theater. And we narrate the memories of our previous experiences with the film even as the film gives memory a tangible existence in the person of an elderly lady with a story to tell.

Labels:

14th century,

9-11,

alliterative revivals,

body,

Chism,

disaster,

Erkenwald,

film,

history,

Hurricane Katrina,

medieval,

memory,

middle english,

narrative,

ocean,

sea,

shipwreck,

St. Erkenwald,

Titanic

Tuesday, April 3, 2012

"And we all shine on . . ."

A lot has happened since I last wrote, and I have a list of posts (on dissertating, on NEMLA) that I plan on submitting to the blog very soon.

For now, however, I want to talk about something else. Two years ago today, my beloved father-in-law passed away. This anniversary is hitting me particularly hard, so I don't honestly have all that much that I can say right now -- words aren't coming that easily, and there are so many stories that I could tell. Too many for a single post though, and they deserve more justice than I can give to them right now.

What I do want to announce, however, is that my incredible mother-in-law has written a beautiful book about Mark, and it's going to be released tomorrow. It's called The Humanity of Medicine: A Journey from Boyhood to Manhood, and you can find it here.

For those of you who don't know, Mark survived what should have been terminal cancer as teenager, and went on to have a miraculously long and rich life. He was diagnosed again with malignant melanoma in October 2009, and while the months (and especially the weeks leading up to his passing) were among the most brutal our family has ever experienced, I will never forget what he told us when we saw him shortly after the diagnosis. He reminded us, in his gentle way, of all the cards stacked against him throughout his life. He was told he wouldn't survive cancer as an eighteen-year-old, and yet he did. He was then told that he wouldn't have children because of the chemo, but he went on to marry the love of his life and they have not one, but three amazing kids. He was told he wouldn't live long, but he lived cancer-free for about thirty years. He reminded us of all of these things, and he told us that he was going to fight hard to beat the cancer again, just as he did before; but if it turned out that this was his time, he told us that in his mind he felt he'd already lived a truly blessed and rich life. Here he was, facing down his own fears and confronting them with grace, but also finding a way to lead his family through the storm; truth be told, he never stopped being a healer, not even on his death bed . . . one of his last lucid conversations involved him asking his doctor (who had known him a long time) how she was holding up. He somehow found it within himself to be strong in the face of immeasurable sorrow and fear -- and not even just then, in 2009, but throughout his entire life. He chose to live his life by looking forward rather than over his shoulder, and that was, in no small part, what he sought to give and instill in all of us in the last months that we were able to spend with him.

I can't express how glad I am that this book is going being released tomorrow. I just made the discovery a few moments ago, and it struck an immediate chord. Loudly and clearly, it reminded me to spend tomorrow/today trying not just to remember and grieve for the amazing person I was so blessed to know, but to live by his example, to try -- as best I can -- to "take a sad song and make it better" (Mark's motto). Because truthfully, we control precious little in this life. The only thing we seem to have any control over is the way in which we digest and respond to our circumstances. True joy lies within those choices -- even in the face of sorrow and loss. This was a truth that Mark knew deeply and well, and I hope that I can do him proud by striving to live in that awareness.

Friday, March 23, 2012

Making Our Way in the World: Musings on Medieval and Modern Maps and GPS

As my dissertation deals in many ways with medieval travel and medieval maps, I've been thinking a lot about my own travels and use of maps. Perhaps some of these musings will make their way into the introduction of my dissertation eventually. For now, I will begin to sketch out some of my thoughts here. Please let me know what you think.

**************************************************************

I've been on two different road trips across the United States. The first was when I moved from California to Rochester, and my old roommates travelled with me across the middle and north of the country. The second was when my mother moved to Rochester, and she and I drove her car down the west coast, across the south, and up the east coast. Both trips were beautiful and serious and silly, just as road trips should be. The topography and company was obviously different, but our mode of navigating was also quite different. My first trip was before I owned a GPS, and we made our way with an atlas, various state and regional maps, and (when Internet access allowed) google maps to help us out. My second trip was with a GPS in tow. We had a US atlas for good measure, but our days were spent following the green line across the screen of the GPS as we followed the highways through the windshield. Each trip was successful, both in the quality of the experience and in the fact that we arrived at our destination, but I can't help but think of the ways in which having a GPS on that second trip changed our relationship to the land around us. I have always felt that driving to a new home helps to make the move, and the distance, real. When my family moved from Alaska to California in my seventh year, we drove our truck from campground to campground, through the Yukon and down the 101. I had flown back and forth many times before that, but that drive lent a gravity to the move that those flights never did. But on that trip Mom and I let my father deal with navigation. He attempted to interest me in his various, haphazardly folded maps, but I was more interested in what was outside the windows than what was on those complicated pages. On my later grown-up trips, I had a more direct relationship with the planning and the map-looking. And thus I noticed the ways in which locating our own position in the country was different due to the different navigational methods.

With a map, one has a sense of the larger landscape. Even when a map contains a large dot and a "you are here," there's a greater framework for the individual location. That dot is in terms of the big picture. Context may vary according to the map in question, but context is nonetheless abundant. The surrounding area is available, as is an image of how different areas and landscapes and paths connect with each other. When I teach about medieval maps, I talk about how world maps relate to worldview. Maps depict the world metaphorically as much as literally, and medieval cartographers were no less making an accurate worldview as modern ones. In medieval maps, the worldview being so carefully depicted was different from ours, and the aims of the maps are therefore different, but the fact that they give a sense of worldview is the same. If anything, medieval maps are more clear about that fact than modern ones, with the modern notion of depicting the world as it "really is." What medieval world maps can teach us is how constructed maps really are, how much they can tell us not just about how to get from one place to another but also about the cultural mindsets that went into their creation. When my friends and I planned that first cross-country trip with maps and atlases, we gained some of that sense, whether consciously or not. We noticed the shapes of the states and therefore were confronted with the historical and geographical features that forged those boundaries between the individual puzzle pieces that make up this country. We saw how sometimes lakes or mountains manage to cross those borders as well as create them. We became aware of the things that are included in these maps, and the the things that aren't. At any given point in the trip, we could envision our relation to the rest of the trip as well as to all of the areas of the country outside of our path.

When I went on my second cross-country trip, we got some of this as well. I did examine an atlas from time to time, but for fun instead of for practical reasons, since we allowed the GPS to guide us completely. My father having recently passed away, and my mother's move occasioned in response to his death, the trip was cathartic for us. Since my dad loved maps so much, having some along felt right. But, without Dad in the car, the GPS navigated for us. It was a leisurely trip, and we made lots of stops to visit relatives and see sites of historical and/or geographical interest. And our GPS guided us faithfully every step of the way. I love that GPS, and it has never failed me. Mom and I even joked that it saved our good relationship, since getting lost can wreak havoc on family members in the close quarters of a compact vehicle. Yet I began to realize, as we followed its rather insistent directions without question, that watching the GPS screen was giving me a completely different view of the country than looking at a map would have done. A GPS only shows the direct area around the vehicle, and with only the most basic place names and other such features. A large enough river or lake might merit a blotch of blue on the screen, but most topographical features are excluded totally. The most notable feature of the GPS is the green line to indicate that you're going in the right direction (or the dreaded red line to warn you that you're going in the wrong one). In some ways, a map like this might make clear how far from the actual landscape maps actually are, its stylized representation of the country bearing so little resemblance to the view outside the car windows. But there's something else that distinguishes a GPS from other varieties of maps. A GPS gives a teleological view of geography. It's purpose is not to represent the country or region or state or town or neighborhood with any kind of totality but instead to get the driver from point A to point B. Larger context is shed and only the details that serve the purpose of the final destination are included. Anyone who has used a GPS has become painfully aware of this fact when attempting to make an unexpected detour. Dare to stop for a bathroom break or for lunch or to make a spontaneous visit to a roadside attraction, and the harsh tones of a phrase like "Turn back where possible" will repeat insistently until the passengers are forced to turn the sound off until back on the original path. As useful as the device is, it really is about the destination rather than the journey. The people of the Middle Ages had something for this purpose as well: the itinerary. Meant for pilgrims who needed to know how to get to a specific destination, itineraries were long, unfolding maps depicting the road and roadside details needed to find one's way from one place to another.

The aesthetic differences between the mappa mundi, or world map, and the itinerarium peregrinorum, or pilgrim's itinerary, are immediately apparent, as are the differences of purpose. While mappae mundi are aesthetic creations and visual encyclopedias that tell the viewer about his/her location in terms of a larger historical and spiritual narrative, itineraries give the traveler a means by which he/she can accomplish a journey. The former is of little practical use when trying to find one's way, though it may in fact have given people a sense of finding their way in a more cultural and spiritual sense. The second may give some practical guidance to the traveller (though, looking at itineraries, I am dubious of even how much they would have helped a medieval traveller). Finding one's way and locating one's self in the world are the province of each, but in a different way. Perhaps they give a different sense of narrative as well as geography. The way in which biblical and classical and contemporary history overlap on the world maps tells us something about the view of history such maps relate. They're densely textual, but the each piece of text only has meaning in terms of its spacial relationship to other bits of text or features of the map. The visual and the textual are inextricably bound. Itineraries are often colorful and beautiful, but they still give a sense of narrative as linear. They move the viewer from a beginning point at the bottom, before which there is nothing, to an endpoint at the top, after which there is nothing. A GPS is different, of course, in that the destination can be changed on a whim, and that the traveller can enter a new destination for each portion of the journey, but it still privileges destination. The device will do nothing until a destination is entered, and it only functions for any length of time when the car is on and it can be plugged in (helpfully reminding the user not to drive and work it at the same time). It is, in that way, for no other purpose than getting from place to place. Its ever changing screen allows for no contemplative functions, and that's OK. It serves its purpose well. Yet comparing different kinds of maps and navigational tools reminds me of the different ways in which we relate to our geographies, our histories, our lives. As I play with my apps from National Geographic World Atlas and Google Earth and watch as the screen zooms in from globe to individual location, I wonder about the multiplicity of ways in which we can view the world around us.

I've been on two different road trips across the United States. The first was when I moved from California to Rochester, and my old roommates travelled with me across the middle and north of the country. The second was when my mother moved to Rochester, and she and I drove her car down the west coast, across the south, and up the east coast. Both trips were beautiful and serious and silly, just as road trips should be. The topography and company was obviously different, but our mode of navigating was also quite different. My first trip was before I owned a GPS, and we made our way with an atlas, various state and regional maps, and (when Internet access allowed) google maps to help us out. My second trip was with a GPS in tow. We had a US atlas for good measure, but our days were spent following the green line across the screen of the GPS as we followed the highways through the windshield. Each trip was successful, both in the quality of the experience and in the fact that we arrived at our destination, but I can't help but think of the ways in which having a GPS on that second trip changed our relationship to the land around us. I have always felt that driving to a new home helps to make the move, and the distance, real. When my family moved from Alaska to California in my seventh year, we drove our truck from campground to campground, through the Yukon and down the 101. I had flown back and forth many times before that, but that drive lent a gravity to the move that those flights never did. But on that trip Mom and I let my father deal with navigation. He attempted to interest me in his various, haphazardly folded maps, but I was more interested in what was outside the windows than what was on those complicated pages. On my later grown-up trips, I had a more direct relationship with the planning and the map-looking. And thus I noticed the ways in which locating our own position in the country was different due to the different navigational methods.

With a map, one has a sense of the larger landscape. Even when a map contains a large dot and a "you are here," there's a greater framework for the individual location. That dot is in terms of the big picture. Context may vary according to the map in question, but context is nonetheless abundant. The surrounding area is available, as is an image of how different areas and landscapes and paths connect with each other. When I teach about medieval maps, I talk about how world maps relate to worldview. Maps depict the world metaphorically as much as literally, and medieval cartographers were no less making an accurate worldview as modern ones. In medieval maps, the worldview being so carefully depicted was different from ours, and the aims of the maps are therefore different, but the fact that they give a sense of worldview is the same. If anything, medieval maps are more clear about that fact than modern ones, with the modern notion of depicting the world as it "really is." What medieval world maps can teach us is how constructed maps really are, how much they can tell us not just about how to get from one place to another but also about the cultural mindsets that went into their creation. When my friends and I planned that first cross-country trip with maps and atlases, we gained some of that sense, whether consciously or not. We noticed the shapes of the states and therefore were confronted with the historical and geographical features that forged those boundaries between the individual puzzle pieces that make up this country. We saw how sometimes lakes or mountains manage to cross those borders as well as create them. We became aware of the things that are included in these maps, and the the things that aren't. At any given point in the trip, we could envision our relation to the rest of the trip as well as to all of the areas of the country outside of our path.

When I went on my second cross-country trip, we got some of this as well. I did examine an atlas from time to time, but for fun instead of for practical reasons, since we allowed the GPS to guide us completely. My father having recently passed away, and my mother's move occasioned in response to his death, the trip was cathartic for us. Since my dad loved maps so much, having some along felt right. But, without Dad in the car, the GPS navigated for us. It was a leisurely trip, and we made lots of stops to visit relatives and see sites of historical and/or geographical interest. And our GPS guided us faithfully every step of the way. I love that GPS, and it has never failed me. Mom and I even joked that it saved our good relationship, since getting lost can wreak havoc on family members in the close quarters of a compact vehicle. Yet I began to realize, as we followed its rather insistent directions without question, that watching the GPS screen was giving me a completely different view of the country than looking at a map would have done. A GPS only shows the direct area around the vehicle, and with only the most basic place names and other such features. A large enough river or lake might merit a blotch of blue on the screen, but most topographical features are excluded totally. The most notable feature of the GPS is the green line to indicate that you're going in the right direction (or the dreaded red line to warn you that you're going in the wrong one). In some ways, a map like this might make clear how far from the actual landscape maps actually are, its stylized representation of the country bearing so little resemblance to the view outside the car windows. But there's something else that distinguishes a GPS from other varieties of maps. A GPS gives a teleological view of geography. It's purpose is not to represent the country or region or state or town or neighborhood with any kind of totality but instead to get the driver from point A to point B. Larger context is shed and only the details that serve the purpose of the final destination are included. Anyone who has used a GPS has become painfully aware of this fact when attempting to make an unexpected detour. Dare to stop for a bathroom break or for lunch or to make a spontaneous visit to a roadside attraction, and the harsh tones of a phrase like "Turn back where possible" will repeat insistently until the passengers are forced to turn the sound off until back on the original path. As useful as the device is, it really is about the destination rather than the journey. The people of the Middle Ages had something for this purpose as well: the itinerary. Meant for pilgrims who needed to know how to get to a specific destination, itineraries were long, unfolding maps depicting the road and roadside details needed to find one's way from one place to another.

The aesthetic differences between the mappa mundi, or world map, and the itinerarium peregrinorum, or pilgrim's itinerary, are immediately apparent, as are the differences of purpose. While mappae mundi are aesthetic creations and visual encyclopedias that tell the viewer about his/her location in terms of a larger historical and spiritual narrative, itineraries give the traveler a means by which he/she can accomplish a journey. The former is of little practical use when trying to find one's way, though it may in fact have given people a sense of finding their way in a more cultural and spiritual sense. The second may give some practical guidance to the traveller (though, looking at itineraries, I am dubious of even how much they would have helped a medieval traveller). Finding one's way and locating one's self in the world are the province of each, but in a different way. Perhaps they give a different sense of narrative as well as geography. The way in which biblical and classical and contemporary history overlap on the world maps tells us something about the view of history such maps relate. They're densely textual, but the each piece of text only has meaning in terms of its spacial relationship to other bits of text or features of the map. The visual and the textual are inextricably bound. Itineraries are often colorful and beautiful, but they still give a sense of narrative as linear. They move the viewer from a beginning point at the bottom, before which there is nothing, to an endpoint at the top, after which there is nothing. A GPS is different, of course, in that the destination can be changed on a whim, and that the traveller can enter a new destination for each portion of the journey, but it still privileges destination. The device will do nothing until a destination is entered, and it only functions for any length of time when the car is on and it can be plugged in (helpfully reminding the user not to drive and work it at the same time). It is, in that way, for no other purpose than getting from place to place. Its ever changing screen allows for no contemplative functions, and that's OK. It serves its purpose well. Yet comparing different kinds of maps and navigational tools reminds me of the different ways in which we relate to our geographies, our histories, our lives. As I play with my apps from National Geographic World Atlas and Google Earth and watch as the screen zooms in from globe to individual location, I wonder about the multiplicity of ways in which we can view the world around us.

Labels:

cartography,

dissertation,

gps,

itinerarium,

itinerarium peregrinorum,

mappa mundi,

medieval,

medieval maps,

medieval worldview,

Middle Ages,

pilgrim,

pilgrimage,

road trip,

teaching,

topography

Saturday, February 25, 2012

Reducing the Medieval (with an anecdote about dissertating!)

|

| Waimea |

So, here’s hoping I look a lot better on the 13th

of March than I did at Waimea a few Novembers ago! I would post comparative

pictures, but a) there were, quite mercifully, no photographs taken on that

fateful day at Waimea and b) there WILL be no cameras anywhere near me on the

13th of March.

*****

In the meantime, I wanted to share a few thoughts that came to me

as I commented on student questions a couple weeks ago in my medieval literature

course. My students are fantastic, by

the way, and have managed to make the past few weeks a truly innervating

teaching and learning experience – even though we are only three in

number! One of my students brought up

Eve in a recent comment, referring to her as many tend to do — as arguably the

most negative exemplar for women in medieval iconography, the binary opposite

of the Virgin Mary. In truth, however, Eve’s

treatment in medieval literature, as John Flood has recently observed, is far

more nuanced and – in several cases – more deeply sympathetic than we’d

necessarily assume. My student was

hardly at fault for not realizing this, since the negative portrayal of Eve in

the Middle Ages tends to take the foreground more often than not.

In the meantime, I wanted to share a few thoughts that came to me

as I commented on student questions a couple weeks ago in my medieval literature

course. My students are fantastic, by

the way, and have managed to make the past few weeks a truly innervating

teaching and learning experience – even though we are only three in

number! One of my students brought up

Eve in a recent comment, referring to her as many tend to do — as arguably the

most negative exemplar for women in medieval iconography, the binary opposite

of the Virgin Mary. In truth, however, Eve’s

treatment in medieval literature, as John Flood has recently observed, is far

more nuanced and – in several cases – more deeply sympathetic than we’d

necessarily assume. My student was

hardly at fault for not realizing this, since the negative portrayal of Eve in

the Middle Ages tends to take the foreground more often than not.

The process of clarifying my student’s understanding of

Eve’s representation in medieval literature, however, got me thinking about

reduction and its imbricated relationship with proximity. It is so much easier to strip away nuance

—from a person, a religion, a culture, etc. — when the object in question is distanced

from the viewer. I’d even go so far as

to say that the farther away you get from an object, the easier this process

becomes. Many pre-postcolonial theorists

who examine medieval literature have noted as much about the treatment of

cultural others in medieval European literature (the work of Sylvia Tomasch

comes immediately to mind), and my dissertation argues, in part, that the stark

binaries that appear in so many Middle English crusades romances are maintained

specifically because of this relationship between proximity and reduction.

The conversation with my student, however, reminded me that

this ability to be reductive by way of distance can also apply to 21st

century perceptions of the Middle Ages. As John Ganim has observed, the Middle

Ages as a time period is both consistently and conspicuously Othered, and

scholars who invest themselves in the study of it will always be at odds with

the reductive approaches that have been endorsed and perpetuated for

centuries. Because of this treatment,

however, studying the Middle Ages can allow students to become more aware of

how we are conditioned— and how we condition ourselves — to consider and quantify

“things in the past.” Perhaps one of our

broader purposes of teaching these dusty tomes, then, is to invite students to

challenge their own tendencies to strip nuance away simply because the object

in question is – and always will be – profoundly alien.

Monday, February 20, 2012

"Do you feel different than you did yesterday?": Identity and Growing up

This past week I've turned 30, and I've been thinking a lot about age. In my culture, I've reached a new landmark. I'm now in a different category. Perhaps I'm even an adult (though it's hard to be sure). Yet I remember clearly being a child, being a teenager, turning 18 and 21. Those selves were different, and yet they were also me. I am different, and yet I am still them as well. When I look at the images of me in my prom pictures, first drivers license, or kindergarten school photo I know what thoughts lie behind the eyes of the girl in those pictures because I was the one thinking them. Since I teach and write so much about identity, I think it's perhaps useful to think a bit about how age and identity interact in ways similar to and different from other identity categories.

Aging is inevitable; as long as we're alive we continue to age. (Whether we mature or not is another story . . .) And yet I find it important to remember earlier ages, to remember what it was like to be in different positions because of age. Children are disenfranchised and vulnerable, at the mercy of those to whom fate has delivered them. I was lucky enough to have wonderful parents to care for me, but not all children are fortunate in this way. And being a child is scary even in the best of circumstances. Everything is new, and children have little power over their lives, little understanding of the world around them, and little ability to communicate their ideas.

I remember learning to write my name with my grandma. I must have been about three. I felt terribly unjust providing the "i" with dots and leaving the other letters dotless, so I took a bold and unprecedented step and dotted every letter. My grandmother, a wonderful teacher and very patient person, erased the extra dots and explained to me once again how to spell my name. I tried to explain to her that I did understand how to write my name, that I hadn't made a mistake but instead had made a difficult choice in the name of justice. As you might imagine, I simply didn't have the words. Though this is a silly example, I still understand that struggle to express my opinions and beliefs to others. In fact, much of grad school has been about learning to put into words those things that I've always cared about. Dissertation-writing is so painful at times because it's an attempt to think things that haven't yet been expressed and find a way to express them.

I also remember my first day of pre-school. I was thrilled to be entering a world of learning, but I was also painfully timid. I sat at playtime doing nothing. I wanted to go across the room and get the play-doh, but I wasn't sure whether or not I was allowed to play with the play-doh. That distance between my chair and the toy cabinet was too perilous to cross, so I sat alone while other children laughed and played. Yet that day I came home and announced to my parents that I would be a teacher one day. In the safety of my own bedroom, I grew bold in my newly attained school-wisdom. I lined up my dolls and stuffed animals and taught them everything I'd learned. Over the years, I have worked hard to bring out the assertive teacher-self in me. Most of the time, I have succeeded, but sometimes the scared little child in the big and frightening classroom of the world returns without warning. Not only do I remember what it's like to be her, but sometimes I am her again.

I could write endless examples of such moments in my life, both meaningful and mundane. I could write about the sense of desperate grief and dismay and terror when my friend was stolen from her bedroom at night when I was 11 while her mother slept down the hall. I could talk less seriously, and explain my feelings of righteous validation when it was discovered that my first car was stolen (and totaled) by a bunch of 30-somethings rather than by "stupid teenagers," as all the adults had assumed. I could talk about my first breakup or about my cross-country move or the moment I discovered that my father had died. All of these represent different moments of my life. I can neither fully exist in those moments again nor be fully detached from how I felt in them. They work together to make up me.

Time is funny that way. Age is funny that way. We all move inexorably from childhood to adulthood, whatever those terms mean. In fact, age might be the only way in which everyone, without fail, drastically changes identity categories. All one must do is stay alive. At different ages, we exist differently in the world, and the world treats us differently based on how long we've been in it. Of course there are countless factors making up our identity position at any one moment. Our race, class, sex, religion, etc. all impact identity position, as does individual personality. And different times and places define ages differently, as they do these other factors. But age is unique in that any given age is fleeting. We all move from one age to the next and can make the choice of how to treat those people younger than we (or, for that matter, older than we). Perhaps if we can consider how it felt to be in a different identity position because of age we can go a step further and think about how it might feel to be in a different position for other reasons. Perhaps if we learn some compassion for our younger selves, we can extend that to compassion for other people as well. Perhaps it's clear that, while I've grown more cynical with each year, I'm also still the same idealist who wanted to give every letter a dot.

Aging is inevitable; as long as we're alive we continue to age. (Whether we mature or not is another story . . .) And yet I find it important to remember earlier ages, to remember what it was like to be in different positions because of age. Children are disenfranchised and vulnerable, at the mercy of those to whom fate has delivered them. I was lucky enough to have wonderful parents to care for me, but not all children are fortunate in this way. And being a child is scary even in the best of circumstances. Everything is new, and children have little power over their lives, little understanding of the world around them, and little ability to communicate their ideas.

I remember learning to write my name with my grandma. I must have been about three. I felt terribly unjust providing the "i" with dots and leaving the other letters dotless, so I took a bold and unprecedented step and dotted every letter. My grandmother, a wonderful teacher and very patient person, erased the extra dots and explained to me once again how to spell my name. I tried to explain to her that I did understand how to write my name, that I hadn't made a mistake but instead had made a difficult choice in the name of justice. As you might imagine, I simply didn't have the words. Though this is a silly example, I still understand that struggle to express my opinions and beliefs to others. In fact, much of grad school has been about learning to put into words those things that I've always cared about. Dissertation-writing is so painful at times because it's an attempt to think things that haven't yet been expressed and find a way to express them.

I also remember my first day of pre-school. I was thrilled to be entering a world of learning, but I was also painfully timid. I sat at playtime doing nothing. I wanted to go across the room and get the play-doh, but I wasn't sure whether or not I was allowed to play with the play-doh. That distance between my chair and the toy cabinet was too perilous to cross, so I sat alone while other children laughed and played. Yet that day I came home and announced to my parents that I would be a teacher one day. In the safety of my own bedroom, I grew bold in my newly attained school-wisdom. I lined up my dolls and stuffed animals and taught them everything I'd learned. Over the years, I have worked hard to bring out the assertive teacher-self in me. Most of the time, I have succeeded, but sometimes the scared little child in the big and frightening classroom of the world returns without warning. Not only do I remember what it's like to be her, but sometimes I am her again.

I could write endless examples of such moments in my life, both meaningful and mundane. I could write about the sense of desperate grief and dismay and terror when my friend was stolen from her bedroom at night when I was 11 while her mother slept down the hall. I could talk less seriously, and explain my feelings of righteous validation when it was discovered that my first car was stolen (and totaled) by a bunch of 30-somethings rather than by "stupid teenagers," as all the adults had assumed. I could talk about my first breakup or about my cross-country move or the moment I discovered that my father had died. All of these represent different moments of my life. I can neither fully exist in those moments again nor be fully detached from how I felt in them. They work together to make up me.

Time is funny that way. Age is funny that way. We all move inexorably from childhood to adulthood, whatever those terms mean. In fact, age might be the only way in which everyone, without fail, drastically changes identity categories. All one must do is stay alive. At different ages, we exist differently in the world, and the world treats us differently based on how long we've been in it. Of course there are countless factors making up our identity position at any one moment. Our race, class, sex, religion, etc. all impact identity position, as does individual personality. And different times and places define ages differently, as they do these other factors. But age is unique in that any given age is fleeting. We all move from one age to the next and can make the choice of how to treat those people younger than we (or, for that matter, older than we). Perhaps if we can consider how it felt to be in a different identity position because of age we can go a step further and think about how it might feel to be in a different position for other reasons. Perhaps if we learn some compassion for our younger selves, we can extend that to compassion for other people as well. Perhaps it's clear that, while I've grown more cynical with each year, I'm also still the same idealist who wanted to give every letter a dot.

Friday, January 20, 2012

Is there a teacher in this class?

Yesterday I had an unusual first day of the semester. I have never felt so prepared, never so calm, about a new class. I've had the syllabus printed and collated for a couple of weeks, the library workshops booked, the books in the bookstore, the e-reserves online and the films ready for streaming. For the first time, I had really thought of everything. I didn't have a single teaching anxiety dream. The morning of my first class I pondered whether this lack of anxiety was a bad sign or whether it simply meant that I had finally figured things out. I hoped it was the latter. I arrived in class a few minutes early, but not so early as to make the students nervous, and I made comfortable first-day chatter as I handed out my carefully-planned syllabus. As I looked up, I noticed that every single student in the room was giving me a strange look. One brave student finally raised his hand and asked what class I was teaching. When I answered Freshmen Writing, all of the students raised their hands and informed me that they were here for German class. If I had been in a good humor, I might have gotten out my copy of Beowulf and joked that Old English was close enough to German. Instead, I quickly and quietly gathered up my things and moved into the hallway. What I discovered after a few phone calls is that there had been a miscommunication about the class time. I had been told one time and my students had been told another. Further, my students had been told an earlier time -- I had missed my first class altogether.

Even at the time, I knew that this would shortly become a funny anecdote. I wrote my students an email explaining what had happened, and I was aware that it would be OK. Yet what I can take from it is that no amount of planning can account for everything. Part of being a good teacher, I think, is the flexibility to adjust to the situation rather than trying in vain to make the situation fit to a preconceived notion of how things should go. Not that good planning is a bad thing, but that in teaching, as in life, we simply cannot control all of the variables. And that's OK. This will probably be a much more memorable first day than any I've had thus far. If I spin it well, it might even provide us with a shared joke that could speed up our rapport as a group. My class theme this semester is dreams in literature and film, so maybe the feeling of displacement we all experienced will put us in the right frame of mind (I know my pneumonia-fueled fever last semester helped me identify with some of the crazy texts I was teaching). If nothing else, I can feel connected to the dream theme in that showing up to the wrong class on the first day is a classic teaching nightmare . . . Happy beginning of the semester, all!

Even at the time, I knew that this would shortly become a funny anecdote. I wrote my students an email explaining what had happened, and I was aware that it would be OK. Yet what I can take from it is that no amount of planning can account for everything. Part of being a good teacher, I think, is the flexibility to adjust to the situation rather than trying in vain to make the situation fit to a preconceived notion of how things should go. Not that good planning is a bad thing, but that in teaching, as in life, we simply cannot control all of the variables. And that's OK. This will probably be a much more memorable first day than any I've had thus far. If I spin it well, it might even provide us with a shared joke that could speed up our rapport as a group. My class theme this semester is dreams in literature and film, so maybe the feeling of displacement we all experienced will put us in the right frame of mind (I know my pneumonia-fueled fever last semester helped me identify with some of the crazy texts I was teaching). If nothing else, I can feel connected to the dream theme in that showing up to the wrong class on the first day is a classic teaching nightmare . . . Happy beginning of the semester, all!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)